Not many teen romances had won the Carnegie Medal before 1986, but that was the year Berlie Doherty won, somewhat to her surprise, with Granny was a Buffer Girl. She gave the world four love stories for the price of one, with added extras.

|

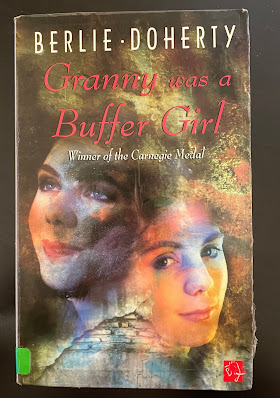

| This Mammoth edition is not the greatest. |

The book had its origins in a series of short stories that Doherty was asked to write for BBC Radio Sheffield and it was inspired by William Rothenstein's painting Buffer Girls in Graves Art Gallery in Sheffield. These stories were then later reworked into a novel.

It's a short novel which begins as Jess, the central character and sometimes the narrator, is about to leave home for a year in France as part of her university course. Her family have gathered to celebrate the life of her brother, Danny. Danny has died some years earlier, at more or less the same age Jess is at the start of the book, though at first we're told very little about him. It's only later that we learn of his life confined to a wheelchair and dependent on others. We never learn the exact nature of his medical condition.

At this family party Jess's grandparents and parents tell stories of their own first romantic encounters. The stories are short and it struck me that each of them could easily be expanded into a much longer piece, or form the basis of a much longer novel. But that, in a way, is the point. Family stories are often like that—I mean the stories told within families. They're simple on the surface, like the chance meeting at a tram stop between a Catholic girl and a Protestant boy that leads to a secret marriage which is later accepted by their parents. That's Jack and Bridie. But you just know that there must be a whole lot more behind that simple story.

|

| I bought this first edition online. It's a great cover and much nicer to read. |

|

| What's more, it arrived in an envelope with these stamps on it! A 45 year old stamp seems to get the package delivered at top speed! |

Themes of being trapped and of searching for freedom run through all of the stories and especially through that of Danny, which is referenced but not elaborated on in the first chapter, and then not returned to until we are halfway through the book. On the eve of leaving home Jess says: "I wanted to tell Mum something that I'd never been able to say to her before. If I left it till I came back home I might never be able to say it. I might be a different person."

We don't find out at this point what was the terrible thing Jess said to Danny, and neither do we find out what was the terrible thing Jess's mum said to Danny. Waiting to find out about Danny provides a lot of the book's suspense and Danny's situation provides a kind of symbol for the whole book. He is trapped—in his body, in a wheelchair, but he loves life (and especially Jess) and makes the most of the short time he has. In fact Jess owes her own life specifically to Danny's request for a baby sister, a request which he makes immediately after his mum and dad have been discussing whether to put him in a home (Mum's terrible thing is to wish he'd never been born). There's a family conference after this at which various important themes of the novel are stated. 'Seventeen years of life that's full and loving is every bit as good as seventy years of life that's cold and wasted." (Bridie) "I was a girl then," says Dorothy, thinking back, 'What's life done with me?" "'There's nothing more worth having than a mother's love,' Jack said softly. 'And a father's,' said Mike."

It's perhaps not surprising that, having known all her life that she was born because of Danny's wish, Jess should blame herself for his death. And, although the family make a point of celebrating lives rather than commemorating deaths, Danny's death is grim.

You might think that in a book offering four teen romances love would be the key to freedom, but it's not so, or never completely so anyway, and as Jess's grandad Albert tells her 'love's more than kissing and cuddling.'

This is not a sentimental book. There's Dorothy, the buffer girl of the title, who dances with the boss's son at the Firm's 'do' and thinks she's found love and an escape from poverty. Except that, in a kind of inverted Cinderella story, he fails to recognise her when she emerges filthy from the factory at the end of the day. So Dorothy marries the boy next door and later feels regret about the life she's lived. Or there's Dorothy's sister, Louie, who is trapped in a bad marriage to a brutish husband, and who sees freedom beckoning when the husband is paralysed by a stroke, only to have that freedom snatched away again when Jess claims to have read his mind through his eyes and says he wants to go home.

Jess's dad, Mike, who doesn't have much luck with girls as a teenager, meets Josie just as he's going off to do National Service and it looks like freedom (and happiness) will be his. But then Danny is born with his mysterious medical condition and their life is changed. They're trapped looking after their son. And Jess herself has her first romantic encounter at a disco and falls in love with a man who turns out to be married with a baby. So she settles for her best friend's brother, a bit like Albert and Dorothy all those years ago. Or maybe not, because what will happen to Jess in the end is left open at the end of the book. She just knows that she will never be a child again.

There's another image of freedom in the chapter which follows Danny's death. Jess's younger brother, John is a complete contrast to Danny and escapes to the Derbyshire moors at every opportunity on his bike. On one of these rides he finds a pigeon that can't fly and brings it home, where his dad insists he takes it back to where he found it. The symbolism of all this seems a bit obvious—Dad's just been freed from the burden of looking after Danny and he can't face going through it again—but when John brings the bird back again, having cycled miles and tried unsuccessfully to get it to fly, Dad relents and helps John to look after it. They end up keeping homing pigeons, birds which are free to fly but always come home.

The book's great strength is its refusal to make quick and easy judgements. Human relationships are always more complicated than we imagine, especially as self-obsessed teenagers. There's an awful lot of thought-provoking material packed into 126 pages and, as an adult reader, I would have loved to have more time to get to know the characters, and perhaps to have seen these dramas presented more subtly. Yet at the same time I can see how well it works as a book for younger readers.

Granny is a Buffer Girl is also that rare thing among Carnegie winners, a book about real working class people in a real place, the place being Sheffield. There have been very few of these since Eve Garnett's The Family from One End Street won the second Carnegie in 1937. By my reckoning only Richard Armstrong's Sea Change (1948) and Robert Westall's The Machine Gunners fit the bill.

There are one or two things about Granny was a Buffer Girl which feel a little uncomfortable to a modern reader. There is a chapter in which Jess goes for a walk with her Grandad along the bank of a heavily polluted canal overlooked by abandoned factory buildings. Berlie Doherty captures the surprising beauty of post-industrial landscape beautifully but like Danny's life it's grim at the same time. And on this path they often meet an old friend of Jess's grandad's called Davey: "an awkward, shambling, desperate sort of a man." Jess doesn't like him. There's this conversation between her grandad and Davey:

'Bet you were dreaming about lasses, an' all,' Grandad would say . . . Davey would turn his sheepish sideways grin at him, and then at me, only I wouldn't show I'd seen it.

'Lasses? What did lasses want wi' me? I've never got on with lasses, Albert.'

'Nay. But it doesn't stop thee dreamin' on 'em.'

When Jess meets Davey alone on the canal path one day and he blocks the path and demands a kiss it is no surprise that she shoves him out of the way in horror. What is surprising is that the reader is asked to feel sympathy not for Jess but for Davey, who is distressed by the incident. Albert invites Jess to consider whether her best friend Katie (always loving) wouldn't have handled the situation differently perhaps by making a joke of it. I wasn't at all sure that this incident needed to be here, but its author clearly considered it important as it occupies an entire chapter, the chapter in which Albert talks about love not being all about kissing and cuddling.

The other thing that stood out for me was a moment when Katie's brother Steve is described as having a dance style that he's 'picked up from some of the black kids at school.' This is the first time in my Carnegie reading that I've seen children described as 'black' since Walter de la Mare's Sambo and the Snow Mountains, the story which was included in the 1947 Collected Stories but removed in later editions. I think perhaps that the reason this reference to 'black kids' drew my attention is because it made me realise just how invisible people of colour had been in Carnegie winners up to this point.

Granny was a Buffer Girl is out of print at the moment, but is due to be republished this year (2023). Berlie Doherty has a comprehensive and very active website with much more information about this and many other books and all kinds of other aspects of her long career.

Finally a word for Janni Howker, Highly Commended for the second year running for the brilliant Isaac Campion. I can't help feeling about Janni Howker's books that maybe they were just too good, so that maybe the judges thought that, as with Rosemary Sutcliff, they could afford to wait for the next one, because every book she wrote was fabulous. If so, they were mistaken. The extraordinary Martin Farrell followed in 1994 and the picture book Walk with a Wolf in 1997 but there has been nothing since.

No comments:

Post a Comment