|

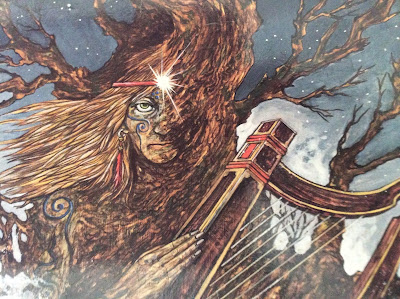

| Taliesin from the Hallowquest pack - Illustration by Miranda Gray. |

'What you're seeing is like a double vision - an actual land and a ghostly resonance which lies on top of it, or perhaps beneath it.'

This is my second chat with my old friend John Matthews, following one a couple of years ago which dealt specifically with John's view of the figure of King Arthur- in turn contrasting it with the responses and opinions of writer, translator and poet Kevin Crossley-Holland and storyteller Andy Harrop-Smith. Since then I have been interviewing a great many people about their view of landscape, both in their novels, poetry, music and images, their lives and other particular aspects of it. Who better to talk to about the particular landscape of the Celtic Otherworld, than John, who has made the study of the land and its stories his life's work.

It's great to be talking to you again, John, and of course, last time we did this it was to talk about the first book in your series of Y.A. novels about the young King Arthur.

However, our connection goes right back to 1998, and concerns one of your earliest ventures into fiction, your remarkable book, 'The Song of Taliesin'. It's a book which would be almost impossible to describe, even when you've read it - something which the quotes on the back by Rosemary Sutcliff and John Boorman ably demonstrate. For Taliesin's world, both in the original; story and mythic poetry, and in your reimagining of all this, are decidedly otherworldly and dreamlike. Do you think that's a fair comment?

I'd like to think it was accesible, but really it's part of a much bigger story, and what makes it at times I suppose less easy to follow. Also, I went very deeply into the Celtic material which is less familiar to most readers. I wanted to give it a tone that was Celtic in the same way as the stories of the Mabionogion are Celtic. This means that there are references that you don't normally find within the more medieval end of the Arthurian legend.

The 'Song of Taliesin' was, I believe, the first small entry in your setting-down of your own version of the whole Arthurian cycle - something which you have continually wanted to find the time to complete - but have never quite been granted it. It's been a long time coming, hasn't it? How long have you been at work on it?

I started work on it when I was 15, which means it's now been over fifty years. That doesn't seem possible really, but I've been kind of living with it in all that time. It's like a huge inner story that keeps going all the time, whatever else I'm writing or thinking about. In fact, at the moment, I'm working on a huge compilation of Arthurian stories not found in Malory's incomparable Morte D'Arthur. Although these are mine, in the sense that they are my words, some parts of the story have been added by me, this is like a run-up to the big novel which I still hope to finish, if spared. I'm also writing four volumes of a series of books for children which describes the life of Arthur from the age of 11 to 18 or 19, This covers everything up to the point where the big book begins.

How did all this start, then: your becoming so engaged with all of this stuff? What's your background, and how does this all fit in?

Like I said, it feels like it's been with me forever. I grew up in a house with very few books, and at the first opportunity I had I joined the Public Library and read everything I could lay my hands on about everything. My parents were seperated and I lived with my mother who was not very well-educated. my father wanted me to go to Oxford, but that never happened because he died when I was in my teens and there was no money to send me to college. So basically, I educated myself, by reading everything I could about the subjects that interested me. These were history - particularly early history, mythology, folklore, fairy tales and medieval literature - which of course includes an enormous amount of Arthurian material. I still remember going into my local library in Kensington and discovering that they had a special collection on folklore, getting permission to look at this, and finding an entire bay of books about King Arthur! Of course I was delighted by this and went home with six books under my arm, read those, went back for six more, and so on until I had read everything there was to read there. Sometime afterf this I discovered T.H.White's 'The Once and Future King', and as I read this I knew that I had found the subject I wantred to write about. At that point I simply sat down and started writing. That was the beginning of the big book that is still happening. I still have those early versions. Now when I look back they seem of course very childish and clumsy, but in some ways that original vision, which has a lot to do with magical things going on in forests, have really changed that much. Just the style.

| |

| The Song of Taliesin - original cover art by Stuart Littlejohn |

Before we venture off into other worlds with King Arthur's chief bard, I usually ask people to describe the landscape around them. But, as you live in Oxford, I thought it might be more fun to get you to describe your actual house. You and your wife Caitlin live in a fairly unique house, don't you - which you've described as a 'book cave'.

It has been called that a lot. It's probably a fairly good description. Last time I even attempted a count it was something in the region of 20,000 books, of which quite a number are Arthurian. My office, where I'm sitting now is full. from floor to ceiling, on every wall with Arthurian texts: novels, poetry, plays, even music where I can find that. I have pretty much every Arthurian text written during the Middle Ages that's available in English. I have figures of Arthurian characters all around, not to mention a small collection of replica swords from the medieval and older periods. So I suppose you could say I'm surrounded by Arthuriana. I even have figures relating to the Star Trek TV series, which I always saw as a kind of Arthurian saga. The deck of the Enterprise is a Round Table, Captain Kirk is King Arthur, Mr Spock is Merlin, and so on .

Going back to that early book, something appealed to me directly about the stories in 'The Song of Taliesin', which caused me to become lost in them and more or less wear them like a coat. My only answer was to explore them at an even deeper level, which I chose to do in the form of a stage show and later double CD based on that show.

Could you describe a little further your intentions for that book and perhaps provide us with some more information about the figure of Taliesin and his story.

I wanted to take the story back to the earliest times, roughly 6th century Britain, but keep some of the later medieval magic that is much in evidence in Malory, Chretien de Troyes, Wolfram von Eschenbach - all those great medieval authors. I wanted to be mysterious and I wanted it to be mythical. You remember that all of the stories in 'The Song of Taliesin' and the one that followed it, 'The Song of Arthur', were separated by poems that were written by me in a style that I hoped was similar to that of the bardic poetry that survived and that is attributed to Taliesin. Taliesin the Bard is a man who actually lived in 6th century Britain and left behind a series of mysterious enigmatic poems which I and my wife Caitlin have translated. I think it was these as much as anything that got your attention, and I still think that your interpretation of the stories and poems in the play this became managed to capture the spirit of what I was trying to do.

It's probably important to explain that there are really two Taliesins - one actual, and the other one supposedly, and the other supposedly mythological, as well as two entirely different sets and styles of poems. Could you set the two in their correct context and say which of these you were most drawn to and why.

You're right. There really are two Taliesins. The historical one that I mentioned, and a mythological one who somehow embodies the deepest and most profound aspects of the Celtic world. He was clearly perceived in this way by his peers, because when the Christian monks began to collect and transcribe the poetry of the early period in the 13th and 14th centuries, anything strange and mystical was assumed to be by Taliesin. It's this mythological character, just as it's the mythological aspects of Arthur, that really fascinates me. I love thr stories of the possible historical Arthur. I've even worked on a book suggesting a completely different figure to the ones usually quoted, but it's always been the myth that is my first love.

|

| A page from the original Book of Taliesin |

So, John, we are here to talk about the Celtic landscapes, and that nearly always includes the Celtic otherworld. Is there such a thing as a map for such places, or perhaps you could be our guide and tell us the sort of thing to expect.

I wish there was such a thing as a map of the other world! The truth is it's an immense, complicated, mysterious, indefinable place. The nearest I can get to it is to say that it occupies in some way the same space we do. When you look back at the landscape of the Celtic countries, particularly Wales and Ireland, what you're seeing is like a double vision - an actual land and a ghostly resonance which lies on top of it, or perhaps beneath it. Among the oldest Irish literature there's a particularly wonderful collection of tales called the Dindschensas. These are stories that record the mythological, magical associations of the land. So if you're visiting some particular part of Ireland, and you see a particular hill, or a valley, or a lake, you can find a story which tells you which hero fought there, which fairy woman lived under the water, what great battle took place in this landscape. Of course, the stories themselves are part of it. They are a record of an ancient time and an ancient place. Wherever you go in the Celtic world you'll find stories associated with place. Place was sacred, it had sacred associations, gods and goddesses who lived in those places and left traces of their presence behind in the landscape. It's like walking in a living book.

Thanks, John, you've certainly evoked that for us. Now, through his poetry Taliesin takes us into that otherworldly landscape and he does so repeatedly in any number of wonderful, but dense and often confusing poems, which can sometimes feel as if he's speaking in code that only he and a few others can understand. Maybe as an example you could provide us with a few lines of a typical poem and then tell us what is going on.

Well most of Taliesin's poetry , or that attributed to him, is mysterious because we don't know what the references are about. In particular there are a number of poems which are sometimes called the 'I have beens' - this is where you get a long list of the things that the poet has 'become' in a mystical sense. When Caitlin and I were working on the translations of some of these, we realised very quickly that what they really are is records of ancient shamanic jouneys, where you enter a light trance which enables you to see the reality of what is around you. By reality here I mean the real reality, not what we see in the everyday world with our everyday senses. So here is an extract from one of Taleisin's poems which talks about his origins. And of course the real meaning of these is metaphysical. He's not really saying he took on all those shapes though he may have done so in his journeying. What he is saying is - and this is something that Robert Graves picked up in his wonderful White Goddess, and with whom I discussed this many years ago - is the magical element of poetry. Taliesin was a magical poet, just as Graves was a magical poet, and they both drew from the same source - from the land and from the ancient stories and beliefs of the Celtic people in these lands.

TALIESIN'S SONG OF HIS ORIGINS

Firstly, I was formed in the shape of a handsome man,

in the hall of Ceridwen, in order to be defined.

Although small and modest in behaviour,

I was great in her lofty sanctuary

While I was held prisoner, sweet inspiration educated me

and laws were imparted in a speech which had no words;

but I had to flee from the angry, terrible hag

whose outcry was terrifying.

Since then I have fled in the shape of a crow.

Since then I have fled as a speedy frog,

since then I have fled with rage in my chains,

- a roebuck in a dense thicket.

I have fled in thre shape of a red deer,

in the shape of iron in a fierce fire,

in the shape of a sword sowing death and disaster,

in the shape of a bull, relentlessly struggling.

I have fled in the shape of a bristly boar in a ravine,

in the shape of a grain of wheat.

I have been taken by the talons of a bird of prey.

which increased until it took the shape of a foal.

Trans John and Caitlin Matthews

This all refers to the story in which Taliesin is reborn in a number of different forms and shapes, having accidentally imbibed the drink created by the goddess Ceridwen for her son, which gave Taliesin access to all knowledge. It's one of the truly great myths that arise from the Celtic tradition and that still speaks to us today.

Now, of course, John, beliefs were not by any means the same in the different parts of what eventually became The United Kingdom. In those days it was far from that. Is it fair to say that Ireland and Wales hold much more of a otherwordly and mythical tradition and we should concentrate more on them than on than Scotland and England?

Actually, I would disagree quite strongly about this, because both England and Scotland have an immense number of mythological sites and places you can go. You can, for instance go to somewhere like Alderley Edge in Cheshire and find references to Merlin sleeping beneath the hills. In Scotland you can go to Arthur's seat in Edinburgh and feel echoes of the Arthurian legend again. Maybe there isn't quite the same development as you find in Ireland and Wales. As to the difference between the gods in Ireland and Wales - well really there aren't any major ones. Many are the same being with a different name. Or you can get some like Bran the Blessed, who is the same in Irish or Welsh. or you can get the Smith God Goibniu in Irish and Gofannon in Welsh. Basically these are just different names for the same power. They are the power which lies within the land itself, that empowers those who live on it or visit it. So, if you got to one of those places that has a sacred association, don't be surprised if you feel some of that energy. Of course today we are used to not looking for those things, not expecting to find them, and not believing them when we do, but if we really keep our eyes open we begin to see things that connect us with the ancient belief systems of the land.

| |||

| Taliesin's Grave (Bedd Taliesin) eight miles north of Aberystwyth |

Naturally, you don't have to actually venture into other worlds to discover landscape blessed with myth. Do you have any favourite examples of places where you think the landscape comes straight out of the myth, or there feels like there's something special about it?

Oddly enough, some of the places that I feel the strongest connection with actually have nothing to do with the widely disseminated associations as one might think. Tintagel, for instance is a wonderfully evocative and powerful place that always covers up the figure of Arthur for me. And of course, you can go down to Merlin's cave below the cliffs there and feel the presence of that ancient magical figure. But in actual fact there are no real associations with Arthur or Merlin at those places.

Ah, you may remember, John, that Glebe Cliffs in Tintagel is my favourite place in the world and where I went to seek inspiration for writing the second draft of 'The Song of Taliesin'. But I do feel that there is something healing and somehow safe about Tintagel. There must, however , also be plenty of stories which evoke place in this way and the then being in the place reinforces it.

Yes, indeed. Well I mentioned Alderley Edge. There you can find a carving in the face of the rock with water that comes out beneath it. For a very long time this has been known as Merlin's spring. In actual fact it was carved there by an ancestor of the writer Alan Garner, who lives in the area and has explored it extensively. But when you're standing in front of that face you don't think: oh this is only nineteenth century - you think this is the face of Merlin. And the reason you think that is because there is an ancient story that says Arthur and his Knights are sleeping somewhere beneath Alderley Edge guarded and protected by Merlin. So, there's a kind of mixture of place, story and ancient associations that make you aware of them in a deeper way.

Beginning in April I'm going to be exploring the world, work and personalities of the three main members of the group known as The Inklings, particularly through their use of landscape. After the more famous Tolkien and Lewis, the poet Charles Williams is regularly forgotten, but his two most famous poetry cycles, 'Taliesinn in Logres', and 'The Region of the Summer Stars' are slap bang in that odd, liminal and above all otherwordly space, that is so often part of the Arthurian world. Taliesin is also the central figure in both of them. As a brief flash forward, perhaps you could tell us what makes you love Charles Williams and his work?

I think Charles Williams is one of the most neglected of the Inklings. In fact, he's probably the most original. He was an incredibly good poet and he wrote some of the finest poetry of the 20th century. His cycles of poems, which you mentioned here, are extraordinary and should be required reading for anyone interested in King Arthur. Williams himself was a profoundly strange man in some ways, largely self-educated from a very poor working class background, but he taught himself to a degree where he was able to offer lectures on English Literature, which were almost crammed to the doors. He worked for many years for the publisher Oxford University Press, and during the Second World War, when the company moved its offices to Oxford, Charles Williams went with them and continued to work lecture at a university level. It was then that he met J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis and shared many of his writings with them. I actually have a letter from Tolkien, to whom I must have mentioned something about Williams. Tolkien's response was rather waspish: 'I don't care much for Charles Williams Arthurianisms', he said - adding that he felt the Arthurian legends far too 'Frenchified' and not British enough. I love Tolkien but I disagree with him on that very much. The Arthurian legends are unique in this land, even though they are appreciated across the world, and although many of the stories we have today are written in French, Italian, German and Portugese etc, they retain an essential cultural identity very much connected to the land.

There's a wonderful biography of Charles Williams by my friend Grevel Lindop, called The Third Inkling. It tells his story and shows how much he was involved with the Golden Dawn magical group, which enable him to acquire a deep appreciation of magic and the occult, which went into his wonderful collection of novels. I'd recommend any of these, especially War in Heaven. which tells a contemporary story of the quest for the Grail. Quite a remarkable book. Williams descriptions of magical rituals are second to none. They have a real authenticity about them because of course, he himself had practiced in this way.

Finally, John, at a time when literally everyone in the world has been affected by a single thing, is there anything we can take out of the mythology and other worlds of our ancestors that we can use as teaching, or as a wisdom tool.

The ancestors are still with us. In all kinds of ways. And its at times like this that we can feel most close to them. Many of them lived through times that were every bit as terrifying and uncertain as those in which we find ourselves today. The great pandemic of The Plague which killed off a third of the population of Europe during the Middle Ages: even the more recent flu epidemic which followed on the heels of the First World War and again killed quite literally millions of people - more in fact than those who died in battle. So, I think that even simply acknowledging the ancestors - you don't have to know who they are - is important. Try lighting a candle and dedicating it in your mind and heart to those who went before. That's the kind of memorial that gives us strength.

Thank you, John. I've really enjoyed our chat.

It's been my pleasure, Steve. Thank you.

You can find an abundance of information about John and Caitlin Matthews etc, and their books, courses and CD's here. including the double CD of 'The Song of Taleisin' by Spintale, and other books on Taliesin, King Arthur, The Mabinogion and the Celtic Otherworld.

http://www.hallowquest.org.uk

A large selection of their books can be found on amazon, including several new tarot and oracle sets which include the following.

The Tarot of Light and Shadow, (with Andrea Aste) Watkins 2019.

The Byzantine Tarot, (with Cilla Conway). New edition Schiffer 2021)

The Grail Tarot, (with Giovanni Caselli) New edition Schiffer, 2021

The Beowulf Oracle (with Joe Machine) Schiffer 2021, forthcoming.

The Goblin Market Tarot (with Charles Newington) Watkins 2021, forthcoming.

And following on from John's 'flash forward' to Charles Williams and his recent biographer Grevel Lindop, us the Inklings series will begin on April 8th with Grevel giving us a fascinating insight into the 'forgotten inkling'. After that we celebrate Narnia with Katherine Langrish on the 16th, and Middle Earth on both screen and radio with Brian Sibley.

5 comments:

PS My apologies to Miranda Gray for wrongly attributing her wonderful Taliesin image from the Hallowquest pack to Chesca Potter. Please blame age and dyspraxia.

This is great, Steve! Covers a lot of the questions I'd have loved to ask John, so thanks! And I thought I was alone in loving Charles Williams - obviously not...

What a wonderfully full post, giving us so much to think about and ponder on.

Thank you, Steve Gladwin and John Mathews.

I'm glad you both enjoyed it and John certainly provided generously as he always does. I am a recent Charles Williams convert, Lu, thanks to other enthusiasts like John, Grevel, (whose book is very well worth the read) and Kath Langrish who told me what to read. I think 'All Hallows Eve' is an incredible novel and he is clearly a unique writer and visionary. I don't know what has taken me so long. Grevel should be telling us all about him on April 8th.

Goodness - so much here! Will have to come back to it. Thanks, Steve.

Post a Comment