I tested it out many times with my watch while watching movies and even when writing scripts, counting the number of pages in, to confirm that at these magical points the main plotline undergoes a major shift of direction or gear. Of course you all know this.

Plenty of stories do not quite conform to this rule (usually short or very long or episodic ones) and post-modern writers mess about with it. If there are many subplots or intertwining storylines there will also be distortion, but you can often pick apart these individual storylines and apply the same rule to them.

It's not as if this is deliberate. It seemed to be an intrinsic quality of the way the human mind appreciates the telling of a story and, correspondingly, the writing of one.

Now the novel I am principally engaged on right now has an unusual storyline: it is circular, so in principle has no beginning, middle or end. It's a story (and I don't want to give too much away) that I had been wrestling with how to tell since I first thought of the idea almost half a lifetime ago.

Many times I came to it, tried to write the opening pages and got nowhere. I put it down but it kept bothering me. I knew there was a really good idea in there somewhere. But because it was circular I couldn't get a handle on it, from a dramatic point of view. There were other issues: I needed to do research and at the time wasn't fully capable of it. Some stories have very long gestation period.

Sometimes when you are struggling with a problem like this you read another novel that is quite different and it can give you a sudden insight into your own story, and for me in this particular case it was reading The Raw Shark Texts by Steven Hall which is a very curious book indeed. In case you haven't read it, it is about creatures which exist beneath the surface of a page when you are reading a book which have a life of their own and if you're not very careful they can devour you.

That's quite a powerful idea. It gave me another idea, also, I like to think, powerful. I put it into my mix.

The second new ingredient came from reading a non-fiction book, The End Of Time by Julian Barbour, which argues that time does not exist – except in our consciousnesses. It's quite possible to describe the universe mathematically without recourse to time, he argues.

But if there is no time, how can a story have beginning, middle or end? In fact, how can there be stories at all? Logically, outside of our consciousnesses, stories are impossible. They do not exist 'out there'. We invent them to entertain each other and help ourselves remember stuff.

The third and final necessary ingredient for me to get a handle on my story was to determine the point of view. Up to then I did not have one, other than that of an omniscient narrator. It all fell into place when I realised that I needed a new character from whose perspective everything else was told. Once this had dawned on me, and I'd decided upon who that character was and his relationship to the other protagonists, the story could be written.

First I wrote the synopsis, then a long treatment. I needed to have it all plotted out because it was very complicated. Two years later I found the time to write the first draft and completed it by summer 2013. I left it for nearly a year and then completed the second draft last month.

I then thought I would try an experiment, and I looked at what happened precisely one quarter, one half, and three quarters of the way through the draft. Lo and behold, there were the plot points – in exactly the places where the theory said they should be.

How did this happen? I have a hypothesis, but that's all. Even though the story is circular I had to start it somewhere. Given that my narrator is deliberately telling the story for the benefit of another character in the novel, then the story begins at the most significant entry point for him. He then recounts the story until he reaches the point at which there is a suitable ending for him. This is just his perspective on the events.

Another character might have begun to describe the events at a different temporal point. Nevertheless I chose the character of the narrator, and therefore I am ultimately responsible for choosing where the novel starts to describe the circle of events, and it made total sense to start it there once I had made that choice.

I am incapable, however, of working out whether the final emergent structure is subconsciously imprinted into the novel because it is so deeply engrained in my own mind – as a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy – or whether it would have been there anyway. I know that I needed to establish the characters and the situation before the story could really take off, and I know that the pacing and dramatic intensity needed to increase as the narrative progresses. So I surmise that I had probably adopted the structure and these principles without deliberate intention.

It's vaguely satisfying to know that this happens automatically but also slightly disturbing. I have felt, at times, like dividing the chapters or episodes up and randomly shuffling them to see if anything interesting emerged from the new ordering, but intuitively I suspect that might be a waste of time. An interesting experiment nonetheless. Perhaps I still ought to do it.

I think Barbour is right, and time – therefore stories – do only exist in our minds. Story structure is a necessary consequence of consciousness because we cannot appreciate what comes later without knowing what has come before – whether the story is true, historical, or fiction. We also need to be made to care for the characters before we are motivated to turn the page.

We are prisoners of time and so bound to the logic of narrative. We seek beginnings, middles and ends even where there are none.

I wonder if any of you have similar experiences your own writing processes?

6 comments:

This is really interesting I have never heard of this 3 act structure(I am shamed by my deep ignorance!) and I instantly want to go and see if my books conform... As an anthropolgist, though, I am very aware of Claude Levi-Strauss's theories that stories all around the world are structured in a way that reveals the universal structure of the human mind He was particularly talking about oral traditional stories, and his theories were more about the use of archetypal oppositions, transformations and reversals. It doesn't really work for written texts (nor did it actually work all that well for the oral stories he analysed. I suspect that your neat 3 act structure is a Western literary tradition, and one of the reasons it gets reproduced is precisely, as you say, because we have internalised it through reading so many texts/films/plays told that way, and it therefore feels 'right' and satisfying to us.

Well explained - yes it feels like stories take a natural 'shape' that reflects not only the structure of our minds/thinking but of the world itself. I'd be interested to know if it's just Western, though. Joseph Campbell studied myths from all over the world and found common elements worldwide, which he called 'The Hero's Journey' - not sure what conclusions he drew about the 3 act structure of plot arcs though? Does anyone? I'd be interested to hear if anyone knows. Apparently some Japanese literature is less 'plotted' and more about 'moments'? I could be completely wrong though.

I have my own personal mantra: 'Fiction is memory'.

Meaning, fiction does not mimic real life (which would be impossible anyway). It mimics how we remember real life.

When we remember an event, we instinctively place it in a narrative: the events that led up to the big moment, the moment itself, and how it affected us, and the consequences of it. None of which you can know in real time - these things are only possible in hindsight.

Fiction works the same way. So when we tell a story, we are not creative a counterfeit event - instead, we are fabricating false memories.

(It's one of the reasons I distrust the first-person present-tense narrative voice, as it lacks the hindsight that would enable the narrator to focus on what's actually relevant as opposed to, say, the nearby smell of Bisto gravy.)

This is very interesting. I don't know whether this really is just a Western tradition. Fairy tales seem to have very deep roots that link many different cultures across the globe.

My novel Alice in Love and War was what I'd call a road movie novel. When I was planning it, I was worried that it might trundle along monotonously, and my son told me that a road movie always has a bit in the middle which is in a different location where some reversal or change takes place that determines the course of the rest of the story. He also said the hero usually meets a character there who may seem unimportant but whose significance is revealed later. When I looked at my plot ramblings I saw to my astonishment that I already had all this in place - even to the mystery character.

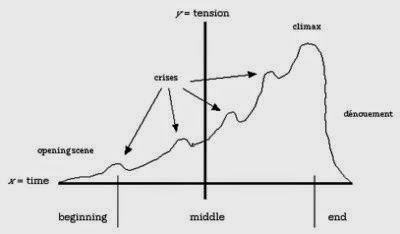

It makes you think that perhaps we may worry too much about our plots and that it all resolves itself naturally anyway. The trouble is, you need to believe that it's sorted before you can start writing, which is why these diagrams are useful. I always draw a diagram like your second one (the first one looks worryingly like a tennis court).

@Ann: Yes, it does look like a tennis court, I hadn't seen that! Perhaps Andy Murray should have studied it and made his third act in differently this week.

In my experience it's good to know this stuff about structure because it saves quite a lot of time in plotting. I'm very familiar with Joseph Campbell's Heroes Journey. Both this and Syd Field's work were deployed by George Lucas when writing Willow and Star Wars. Star Wars was explicitly modelled on Joseph Campbell's theory. This resulted in the popularisation of the latter's work and a vast number of script writing courses being constructed around Joseph Campbell and Syd Field's precepts. This perhaps explains why so many Hollywood plots since then are similar or follow a similar course.

@Nick But is how we remember real life not itself influenced by storytelling techniques, especially as it becomes reinforced by the way we relate sequences of events (which are of course different from stories) to our friends? We make them into stories to make them more interesting. But what does interesting mean? It means that the listener must care and want to know what happens next and subsequent events are not random but link back to earlier ones. The smell of Bisto gravy might be important if it was a clue as to who committed a murder, for instance.

@Heather: the hero's journey is indeed a three act one. It consists of the call to action; the quest or action itself; and its conclusion. In long epics there may be mini-journeys within them, or the second act can be really spun out.

@CJ Busby: I do believe that Campbell built upon Claude Lévi-Strauss's theories.

Interesting, thanks.

Post a Comment