Part One - The Woman From The Sea

Selkies and the tales of them have been important to me ever since 1995, when, following a magical druid retreat to the island of Iona, I was given the gift of story. That particular story has resonated with me ever since and entered into my life and relationships, in love and even in death.

|

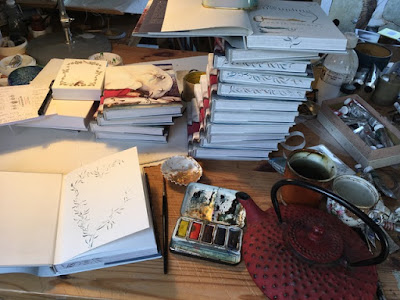

| The book that started all the trouble! |

And yet the odd thing is that I know very little about selkies other than this one tale. This is not so unusual for me because as a storyteller and a writer I have tended to latch on to one particular story, or aspect, rather than attempt further explorations. Sometimes perhaps, I have been disappointed with what I've found, and equally there are times when something has just been one glorious one-off.

Over the next couple of months a number of writers, storytellers and filmmakers will be giving their own opinions about selkies, as well as describing their own encounters and inspirations. In an odd kind of way all of them are connected either to me, or to the story I first read in 1995, but before we get to them, here is a story about a story.

Sometimes a story follows you around. As a wannabee storyteller on a workshop with Ben Haggarty at Bridgwater Arts Centre in Somerset in 1994, I was given my first story. This was 'The Juniper Tree', one of the darkest of all of the tales of the Brothers Grimm, and yet one which passes quite clearly from unrelieved darkness into light so bright it almost, but not quite, wipes out the memory of the darkness.

I've told the story many times since and found it one of those stories which most drive me forward as a storyteller, one of those I am most fully engaged with and become almost part of as I'm telling it.

I have also told that selkie tale of 'The Woman From the Sea' many times, but in the process of telling it, it seems to have become a bit of a rescue tale, where, quite often the person being rescued is me. And yet I also have a deep problem with this tale, one that although I have tried to resolve, I still have problems with.

For those who don't know the basic plot of 'The Woman From the Sea', it's essentially about a fisherman who steals the young woman's skin as she and her folk dance naked on the sand, and doesn't allow her to retreive it. Instead, as her people go back into the sea, the sea woman cannot find her skin because the besotted fisherman has hidden it. She eventually has no choice but to go ashore with him. There he takes the traumatised young woman to the kirk where he awakens the astonished minister and has him perform the marriage cermony there and then.

A convenient blanket is - as so often occurs in traditional tales - covered over the awkward section of the weddding night and the first few years that follow, and the next time we meet the couple they seem both happy and settled with three children, two boys and a girl, who they clearly love very dearly.

One other piece of information is given to us, which may have actually occured more times than the once that is mentioned. On a regular walk along the cliff-top path, the couple see a great bull-sea rise from the sea and bellow its loss. The woman, (who is rarely given a name, but we'll call her Ailsa today), tries to pull away from the man, but he restrains her and of course without her skin- which he hid away somewhere safe on the first day - she is helpless. Here's the next part of the story.

"Seven years after the marriage Ailsa is in the kitchen, humming a tune to herself, keeping an eye on the bread in the oven, which is giving off the most wonderful smell, with flour on her arms and that stray lock of hair, so loved by her husband, which keeps falling into her eyes. The bees are buzzing in the hives and the children are playing in the barn as the swallows of late summer swoop in and out of it. Ailsa smiles as she hears them, loving them just a little bit more because of it.

And then their voices change, the sense of good-natured play being replaced by something altogether different in their tone. And their mothe, where normally she might not have taken much notice, feels drawn to listen.

"What is is?'

'I don't know. Poke it down!'

Why should I. Uurgh.'

'Because you're the oldest.'

'It's slimey. No, not slimey. But it is cold and damp.'

'Like a skin!"

There is no easy way to describe how fast the rest of it happens, or the speed of the woman as she throws off her scuffed shoes and apron and runs from her kitchen towards the barn. And the children barely have the time and words to tell her before she is grabbing the skin from out of their astonished hands and running, running, up towards the cliff. When she throws off her dress and everything else and, now naked, keeps on running, the children giggle at her funny antics, but her husband has come from the fields in a hurry, some premonition having suddenly come upon him, enough for him to down tools and head upwards - to meet his sea wife running from their bothy from the other direction towards the sea.

As she grabs hold of the skin more firmly and that same bellow roars out of the sea, the fisherman knows, the moment before she leaves him, that in that moment he has lost her. She looks at him one last time with the grey green restless eyes of her kin.

'Farewell Donald Campbell', she smiles. 'For you are a good man and despite the manner of my taking, you have been a good and kind husband to me and father to our children. But I have my skin now and I must return. I will never forget you, nor my shore family.'

With a silvery twist Ailsa, the woman from the sea has gone, and the fisherman is left to explain to their distressed children how this is not just a game, but the reality they must now all bear."

I can't remember when

and how it came about, but there came a time when I couldn't bear the

idea of the poor selkie being so homesick, having been wrenched away

from her life in the sea and her family and basically forced into a

marriage with all that that involves. The idea of people suffering and being unable to help themselves from crying has always bothered me, and that's why I can't stand torture scenes or distressed children and old people. The thought of what was going on behind the story, particularly in those missing years wouldn't let me go.

And here is what folksinger Julie Fowlis said in her interview here in February when I asked her about the figure of the selkie and the selkie tales she heard during her own years on North Uist and later on the mainland.

|

| Thanks to celticweddingrings.com |

I remember the stories of the seals from my childhood, yes, but I’m afraid they were not by the fireside as you might imagine, like in a children’s book. These stories are often quite dark and much of the history and folklore I learned when I was a little older.

The seals represent that liminal space for me, they exist in both the worlds of the sea and of land but truly belong to neither. Or is it both? They exist in a way that we cannot and that makes them fascinating. Also when you look into their eyes they definitely hold much expression and emotion, and when you hear their call they can often sound just like a human cry.

Fascinated, as I was by Julie's talk of the tales told in childhood being so much darker, I tried to get her to explain more, but she - probably very sensibly - would not be drawn further.

But as far as my own 'storyteller's' version of 'The Woman From the Sea' is concerned, at some point I appeased my conscience and at least found a way to stop Ailsa from feeling so homesick.

First I created a scene which follows the forced marriage at the local kirk, where Donald the fisherman brings Ailsa, the lost young sea woman home and tries to show her the things he is proud of, including a rug woven by his grandmother, the turves of peat waiting to go on the fire and - the fire itself. Ailsa cannot understand any of his words, but she understands the gentle way in which they are delivered and she understands not just the fire, but the pictures she will see in it.

'And see the turves of peat there? Well, we need them to be laid on the fire here to keep us warm. Maybe, lass, you'd care to warm your hands.'

And for the first time since she left the sea and was forced on to this cold shore with this big stranger with his blunt ways, Ailsa is glad to do something. She's glad to let him help her to kneel by the fire and then to pick up one of the huge turfs with his help and place it on the fire. Only when the flames are taking it and she has poked and broken it down with the thing of iron can she look properly at what has caught her attention and risen in her throat like a bird of hope. The fire.

This fire has none of the colours of her undersea home. There is nothing of the silver greys, or the blues of all hues, nor of the emerald green of the vast sea cave where her father rules, treasured by coral, wary grey of eye and lord of all his surveying. There is nothing or no-one familiar in it's orange-red heart, but somehow, by some curious miracle it is all there in another form. In a different colour scheme, yes, but all there.

And that was how the homesick and shocked young girl came to grow and cope with all of this new and terrifying strangeness. By finding the heart of the thing she needed within something else, something with a warmth so unlike the sea's, but a warmth and comfort nevertherless. And from that day Donald would find her there regularly, staring into the patterns of the flames and as content as he had seen her."

So there you have it, a storyteller's solution to a storytelling problem which has so often been hidden among all manner of dark and shifting snakes to do with the disempowerment and abuse of women. It's not the answer and I suspect that some of the versions of the tales tales told around firesides in the bothies and forever after are shadowing a darker secret like so many other tales, like for example 'Red Riding Hood' and 'Bluebeard' are. But, for what it's worth, I've done my bit as a storyteller with this one story to try to redress the balance.

But it's odd that this early tale of mine is preceded by a memory of being gifted my first ever tale, 'The Juniper Tree', which of all tales, portrays in a far more graphhic way those themes of disempowerment and abuse, which despite the golden glow of it's ending, can never quite wipe out the memory of the blood pudding and the terrifying cellar. But that's another story entirely, and definitely one for another occsasion.

The version of 'The Woman From the Sea' that I first found and told in 1995 was by Kevin Crossley-Holland, and I will leave it to him to relate in the next part of this series on selkies just how that telling came about. To my knowledge that story and the rest of the collection in 'English Folk Tales' have been published twice more and - as of my recent birthday and courtesy of my partner Rose - I now have the latest edition.

To finish here's the story that 'The Woman from the Sea' inspired me to write. Whereas the first part, the story,'Greys, Blues and Emerald Green' is told from the point of view of the oldest son as an old man recalling through a scatter of memories. The poem which follows it was both inspired by the imagined thoughts of the seal wife herself, and by a stone I painted in those three colours and left in the sea at Criccieth while on a course with Kevin and Catherine Fisher at Ty Newydd. In the odd way of such things I'd picked up a similar stone to replace it and - having left it supposedly safe outside the main room, Kevin came along, and thinking it didn't belong to anyone, picked it up and wrote a poem on it about the sea at Criccieth. Luckily, I found another stone and eventually a certain stone with the poem on it plonked through our letterbox.

NB The last line of the story 'parcels of fish at night' is as clear an indication as you may get about the seal wife's feelings about her husband and children, where on some summer nights she will leave them a parcel of fish on a certain rock.

Greys, Blues And Emerald Green

Mum’s always been different. I notice it and so does Tom. In her own way even little Marie notices it. Dad doesn’t seem to notice. Maybe that’s because he loves her most of all.

There are lots of weird things about mum, that make her mum and make me love her. No matter how hard she tries, mum never seems able to get warm. Why else would she keep a fire in the house all year round? Dad says she likes the pictures in the dancing flames, but I don’t understand what he means.

She doesn’t wrap up warm like Gran says we should. Mum’s happy with her bare feet and old dresses of greys, blues, and emerald green. She’s happy to run about foot slapping on the sand playing chase and tag. She’s happy to stand on the windswept cliff top and laugh as the wind fills her dress like a sail and almost - but not quite, takes her up with it.

How can you live somewhere like this? Mum won’t go near the sea, but dad says it’s not because she’s afraid of itBut instead of going in, she’ll stand well back holding our towels for us when we shiny slip like wet seals from the water. She’ll rub our hair and shriek as we shake ourselves like dogs. Sometimes I’ve known her run her hands over our hair and shoulders, catching and tasting our salt, but she’ll never go in the sea.

I know people drown at sea. I know a ship will go out and catch the edge of a ridge or storm and drag men down to terrible death. I know the king of the seal people has all the human drowned as slaves, lighting lamps in his great underground cavern of greys, blues and emerald green.

Mum’s a wonderful storyteller. At night, after we’ve wolfed down the day’s catch - the tang of mackerel, the rubber of squid, the softness of sea trout -, she’ll tell her tales. While dad dozes after his days’s work, our mum tells her marvelous tales of kings and palaces, quests and dragons, clever animals and haunted forests. You’d think she’d know a tale or two of the sea like most people round here but if she knows any, she’s never let on.

The other day a big bull seal rose up bellowing out of the wild, grey sea. Dad looked scared and Marie - who’s only little - hid her face in mum’s apron. But mum! Mum went home and cried quietly for hours. Dad says I’m almost the man of the family now, so maybe he’ll tell me why.

We found something strange up in the barn, caught between the rafters where no-one could see it. We found it by accident but then we were called in to tea and we just forgot completely. Chores and bedtime got in the way, but this afternoon we’re going to go back and poke it down and capture it’s greys, blues and emerald green. Dad will be at work and mum at play in the kitchen. We’ll have our game, Tom, Marie and me. We’ll hold up the skin and run it’s shivery slime through our fingers. We’ll throw it up in the air and kick it about. We’ll put it round her shoulders and I’ll pretend I’m king of the seals.What is born from the sea must return to it.

That afternoon we all realised why our mother was not like other people’s. We realised why the orange fire was emerald green to her and why she tasted the salt on our skin. Now we understood why mum could never be warm enough. I can see my father now, heartbroken on the cliff top, explaining to us all why our mother had gone and where she had truly come from.

Time passes. I’m older now with my own sprats, and it would have been so good for her to have seen her grandchildren and thrown them giggling on her knee. But by the time I was old enough to be the man it was too late. All we had left of her was an apron covered in flour - a kicked off hasty pair of shoes. And parcels of fish at night.

|

| Thanks to weingartdesign.com |

In the blues I can still see you.

In the emerald green of the sea.

On the steel grey of the rock’s back.

I am honey tang in your dreams.

While your powerful arms lie restless.

With my tail still; neglected in dust.

A blaze of turf amidst writhing flames.

Pares down raw my sobbing heart.

For my children grown and gone now

A solitary feast lies scattered on a rock.

while pebbles gleam memory on the shore.

Of greys, blues and emerald green.

Greys, Blues and Emerald Green. Story and Poem Stephen J.W. Gladwin for The Raven’s Call Slippery Jacks Press March 21st 2016

| |

| Rush out and buy this most recent edition! |

Thanks to Kevin, who we will be hearing from at the end of the month, but before that who better to turn to for a proper introduction to the strange, haunting and often tragic world of the selkies than writer, folklorist and Spare Oom expert Kath Langrish. We'll see you on the 16th!