I read a lot of fiction. SF, thrillers, detective fiction, literary fiction, all kinds of stuff. In none of it do I find rape, murder, genocide and war occurring so regularly as in the Carnegie Medal winners I've been reading in the last few months. This month I've read Buffalo Soldier by Tanya Landman, 2015 winner (rape, lynching, murder, genocide, ethnic cleansing, American Civil War, Indian Wars) and Salt to the Sea by Ruta Sepetys, 2017 winner (rape, murder, ethnic cleansing, maritime disaster with thousands of deaths, WW2). Did I enjoy them? Not really. Is enjoyment even an appropriate response to these novels? Well, probably not. Are they children's books? No. So why, then, are they not adult books? (Not that that is even a category). The subject matter is at least as extreme as most adult fiction that I read. I'm beginning to suspect that an important distinguishing feature of YA fiction is that it lacks complexity. I know that's a ridiculous over-simplification, but it does relate to Mal Peet's comment that he didn't like YA because he thought it was 'condescending'. And by complexity I mean complexity of meaning, of ideas, and not simply a complicated plot.

Both these books are the result of extensive research and Tanya Landman has been very clear in interviews about the danger of allowing the research to show through in a novel like this. I'm not sure she entirely succeeds in stopping that happening, but young readers would learn a lot from this book, and indeed many reviews say just that: I learned a lot. The quality of the writing will no doubt pull readers through to the end, although the plot devices which link the whole, slightly rambling story together do feel a bit clunky. But then, I recently re-read Our Mutual Friend by Charles Dickens and the plot of that well-respected novel creaks even more. But Dickens is a writer who uses symbolism and metaphor to deepen the effect of his stories. In Our Mutual Friend the River Thames runs through the book both concealing and revealing the dead and the living. There are people who seem to be dead but are alive, people who are alive but pretend to be dead. There is layer upon layer of meaning, whereas Buffalo Soldier is essentially a simple, linear story whose theme is freedom. Simplicity is not necessarily a bad thing, and complexity is to be found even in picture books for the very youngest children, but I'm just trying to figure out why books with such adult subject matter, books about adults who aren't even all that young, end up being marketed to a specific age range rather than to all adults.

My greater difficulty with the book, however, was with Landman's decision to tell the whole story in the first person in the voice of Charley O'Hara, a newly-freed slave girl. That bothered me, not because of cultural appropriation but because it undermined my trust and made me question the character's authenticity. I think I might have been OK with it if this had been a third-person narrative. Then the author wouldn't have been pretending to be the character, there would have been opportunities for other points of view and there could have been a certain authorial distance. I have no problem with authors writing about characters with different race, ethnicity or gender from themselves, but the first-person narrative here made the novel less effective than it might have been.

While I was reading about white people writing black characters the Uncle Remus stories of Joel Chandler Harris came to mind. I fished out my 1883 copy of this book and then started reading about Harris on the Internet before realising that a) Harris is a controversial figure (I think I already knew that) and b) Harris's Uncle Remus stories have been incredibly influential both on children's fiction and on the wider literary world. They are also a perfect focus for discussions about cultural appropriation. Alice Walker, for example, wrote a piece called Uncle Remus, No Friend Of Mine. She grew up in the same town as Harris and said, 'he stole a good part of my heritage.' All this is too much for this post, but I'll return to the subject once I'm done with the Carnegie.

My reservations about Salt to the Sea were similar in some ways to those about Buffalo Soldier I can only admire the vast amount of research that went into this book, and its intent to inform readers about the 'worst disaster in maritime history' in which about 9,000 people died when torpedoes from a Soviet submarine sank an overloaded passenger vessel carrying refugees from Eastern Europe away from the advancing Soviet troops. I was also very grateful for the maps on the endpapers. But I found the narrative structure of the book incredibly irritating. We have four parallel first-person narratives. One character tells a tiny part of their story, usually in just a few pages, then the next character takes over, then the next and the next, then back to the first character again. This never varies and it wore me out.

As for the characters and the plot, well, there was good and very bad. Alfred, a German sailor, is an almost complete caricature whose dreadful skin condition mirrors his corrupt and revolting soul. And there is a slightly Dan Brown-ish plot strand about the fabled 'Amber Room.' The two female characters, Emila and Joana, are more rounded and convincing, and all the characters are linked by the idea that each of them has a secret. I can see that when you're telling a story where every reader knows that the characters are going to get on a boat and the boat is going to sink, you're going to have to do something to preserve the narrative tension, so we have those secrets and the 'Amber Room' and of course we have a love story. But really, that love story is a bit of a damp squib. It is certainly not Leo and Kate on the Titanic.

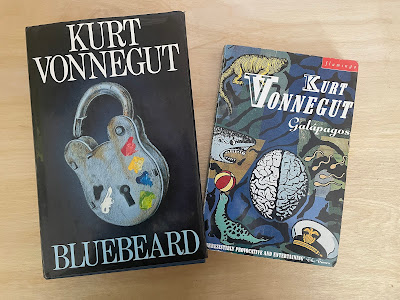

If you want a book about war and genocide in the 20th century I recommend reading Bluebeard by Kurt Vonnegut. It has stuck in my mind for over 30 years since I first read it, but while I remembered vividly the book's extraordinary climax I had completely forgotten that one of the major characters was a writer of Young Adult fiction. She's called Circe Berman and writes Judy Blume-like books under the pseudonym Polly Madison. Her books are good, by the way. Paul Slazinger, a literary novelist and friend of the narrator thinks they are 'the greatest works of literature since Don Quixote'. Others aren't quite so sure. Librarians, teachers and the grandparents of teenagers suggest that they are 'Useful, frank and intelligent, but as literature hardly more than workmanlike.' Kurt Vonnegut's view on the matter remains a mystery.

Bluebeard is a very funny and complex book about grief and how we deal with it, and it served to remind me that there has been a certain earnestness and lack of humour in many of these grim Carnegie winners I've been reading, so it is with considerable relief that I turn to One by Sarah Crossan, which won the Carnegie in 2016.

This novel about conjoined twins is funny, moving and startlingly unsentimental. This is another first-person narrative (I read somewhere not so long ago that this is one of the identifying features of YA literature) but in this case I wasn't at all bothered by a young Irish writer imagining herself into the body of Grace, one half of the pair of twins. I wondered why this was and I think the answer is twofold. First, Grace does not speak with any kind of an accent. She is simply herself, articulate and vivid.

'We take the train home/ with Jon/ and pretend we can't hear all the words around us/ like little wasps stings.'

Jon says he can't imagine what it's like for them.

'"It's like that,"' Tippi tells him/ and points at / a woman across the aisle with a phone/ aimed at us like a sniper rifle.'

I should have mentioned that this novel is written in a kind of blank verse. I had my doubts about this, since at first glance it did at times seem more like prose written out in a different way, but the technique quickly grew on me especially because it gave the writer so much scope for different kinds of emphasis. It was beautifully easy to read. And actually, now I think of it, it's reminiscent of Vonnegut's style, splitting the narrative into very short sections. It also leaves space for the reader's imagination to fill, literal space on the page, but also space in your head. The book has 430 pages but barely 30,000 words of text, which is very short for a YA novel these days.

So, why was I never for a moment worried that this was a book based on research by an author writing about a situation of which she had no direct knowledge. Well, it's because Sarah Crossan makes her characters live. Or rather, her characters in this book live for me in a way that the characters in the books I discussed earlier didn't, for me. There's just as much research gone into One as into Buffalo Soldier or Salt to the Sea, but the book isn't only about the ethical dilemmas confronting conjoined twins and their parents and medical practitioners when they have to consider separating the twins. This story is about Grace and Tippi, about who they are, about how they deal with life and death, about how they relate to the people around them. In Buffalo Soldier and in Salt to the Sea I felt I was being educated about the American West, about WW2. I always felt the characters were secondary to the mission. One is a remarkable feat of imagination from Sarah Crossan. I loved it, and have no intention of spoiling your enjoyment by telling you any more about it. Just read it, if you haven't already.

But to return to WW2, as the list of Carnegie winners has so frequently done. J G Ballard reviewed Bluebeard when it was first published and said this about Kurt Vonnegut:

'For Vonnegut, the most significant events in his life seem to have been his experiences as a captured American soldier during the Second World War, which formed the core of Slaughterhouse 5, and some moment, presumably during the 1960s, when he realised that the next generation had learned nothing from the tragedies of the war, and had even begun to lose all sense of its own past, that great casualty of American culture.' (The Guardian 22nd April 1988)

We're a few more generations down the line from the 1960s now and there's no sign of humanity learning any lessons. If Buffalo Soldier and Salt to the Sea help to remind this generation that we need to do things differently they will indeed have been useful. I don't think Vonnegut would have been optimistic about the prospect of that happening. His (fictional) solution to the problem of how to make human beings behave better was to have us evolve, a million years into the future, into furry seal-like creatures with flippers and small brains who can't do much harm to anyone or anything. That's in his 1985 novel, Galapagos.

In the mean time Vonnegut has some things to say about 'keeping grief away'. Here is Circe Berman, the YA author whose husband has recently died and who has been keeping Rabo Karabekian company over the summer, but is now returning home:

'I asked her if she would write. I meant letters to me, but she thought I meant books. "That's all I do—that and dancing," she said. "As long as I keep that up, I keep grief away." All summer long she had made it easy to forget that she had recently lost a husband who was evidently brilliant and funny and adorable.

"One other thing helps a little bit," she said. "It works for me. It probably wouldn't work for you. That's talking loud and brassy, and telling everyone when they're right and wrong, giving orders to everybody: Wake up! Cheer up! Get to work!"'

Pau May's blog/book pages are here.

No comments:

Post a Comment