So, here we are in the 1990s and we're starting to see more and more books about 'Issues'.

In 1991 Berlie Doherty tackled teenage parenthood, and you might say that in 1992 Anne Fine was in the same territory, although while Flour Babies touches on some of the same issues as Dear Nobody it's also funny and poetic and beautifully constructed. It absolutely avoids any kind of preaching and I love the way the words and tune of an old song are woven into the final third of the book and contribute to its transformative climax. This book has a tremendous final paragraph and I do love a good ending. It's a shame I can't quote it but that really would be a spoiler.

Then in 1993 as a complete contrast there was Stone Cold by Robert Swindells, a bleak book with a central character who is all victim and has no agency whatsoever, and apparently no hope. It's a book, almost a documentary, about teenage homelessness, dressed up as a thriller about a serial killer preying upon homeless youths in London. I once wrote quite a grim book myself, all about death and stuff. My editors told me I needed to leave the readers with some hope at the end and I did try, but they still didn't publish it. Someone published this, though, and it has been much used in schools. It's not a book I would have ever wanted to read, but it has a good number of positive reviews on Amazon from young readers. I wonder if its grimness makes them feel glad they still have a roof over their heads? It is, without doubt, a cautionary tale.

Theresa Breslin's 1994 winner, Whispers in the Graveyard is an 'Issue' book too, the result of a conscious decision by its author to write about dyslexia and its impact. But as Theresa Breslin says on her website '... no point wittering on about dyslexia without a good going tale. Without a "story" the book would be that Solomon goes to school, has a rough time, comes home, has a rough time. So what?'

Well, quite. In Stone Cold, Link (the central character) has a rough time at home so he goes to London where he has a rough time, then a rougher time in Camden. At the end of the book he thinks he might try Covent Garden where I'm pretty sure he'll have a rough time. Robert Swindells' answer to the potential lack of narrative drive was to add that parallel story about a serial killer, but the serial killer is a kind of Marvel comics character and the element of caricature sits uneasily with the 'realism' of the street scenes.

Whispers in the Graveyard, on the other hand, feels like a completely organic melding of horror and realism, and when you read what Theresa Breslin says about the book's creation you can see why: "It meshed together unlike anything else I've ever known - the solitary grave, Solomon's father, the stories, the presence of evil inside everyone, the power of words, the infinite resource of the human mind, - it all came together."

It is a brilliant book - I read it when it came out, and it is still just as good today. And it is, I should mention, only the second Scottish book to win the Carnegie. It contains no easy answers, and has completely convincing school scenes, great dialogue and genuinely chilling horror. And it has a great ending! It's funny how often people talk about the beginnings of books and how seldom about the endings, but I guess it's the spoiler element at work. I might get around to doing a top ten of Carnegie winners' endings one day. I already know the worst ending though - it's from The Exeter Blitz by David Rees:

"You sound like some pansy poncy poet. What are you talking about?"

"Exeter. It's a place worth talking about."

I shudder every time I read that, and I haven't spoilt a thing by telling you about it.

|

| Got to say, I've never understood these back to front dust jackets. |

And so to the 1995 winner, Northern Lights by Philip Pullman, the first volume in the His Dark Materials trilogy. Is there anything to say about this that hasn't been said? I re-read it this month and one thing I did notice was the pace of it. It rattles along like a good thriller - you're straight into the action on page one and it never lets up. In fact, it's amazing how short some of the episodes are, like Lyra's stay in Mrs Coulter's flat, and how quickly the action moves from the boats of the Gyptians to the voyage to the North, to the armoured bears . . .

I remember hearing Philip Pullman describe how the idea of the daemons came to him. It's an extraordinary and brilliant idea, and clearly it's the one most people fix on, but I think it's the storytelling that's the key to the book's enormous success. And even though I think that the story loses focus somewhat in the third volume of the trilogy, the ending, with Will and Lyra separated forever, redeems the whole thing. We always used to say when I played in a band that there was nothing so important as getting the ending right. Do that and the audience would forget all the mistakes you'd made earlier, and it's the same with stories. Not that I'm saying Philip Pullman made mistakes, but I got a bit lost in all those battles in The Amber Spyglass and all those Angels and Spectres . . .

As I'm sure everyone knows, Philip Pullman had a lot of harsh things to say about CS Lewis's Narnia books, and about his adult science fiction too. As in: "I loathe the Narnia books, and I loathe the so-called space trilogy, because they contain an ugly vision." (Interview with Huw Spanner for Third Way magazine, 2002). The irony is that I've always felt that those very works by CS Lewis are major influences on Pullman's own creation. Pullman does say in the acknowledgements at the back of The Amber Spyglass, "I have stolen ideas from every book I've ever read," but I don't know whether he's ever specifically acknowledged his debt to Lewis. I'm thinking particularly of the world of the mulefa which Mary Malone enters, and which, in feel, reminded me very much of Lewis's Perelandra - and isn't the idea of moving between worlds through a kind of portal very similar to the way you reach other worlds in the Narnia books?

That Huw Spanner interview is here, and it's excellent. Among other things Pullman is insistent that his overriding concern is to tell a story and is completely open to the idea that there might be artistic flaws in his book. As he says in the interview: "Artistic perfection is not achievable in anything much over the length of a sonnet."

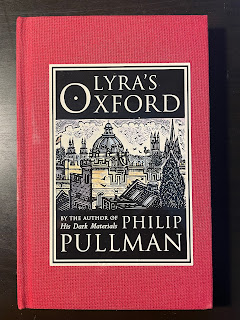

Perhaps that's why I still think Clockwork is his best book. It's short, perfect in every detail and perfectly complemented by Peter Bailey's illustrations. I also like Lyra's Oxford, a delightful miniature add-on to the main His Dark Materials trilogy.

Northern Lights is that rare thing, a Carnegie winner that enjoyed enormous commercial success. And in case you weren't aware, the initial print run was small, so a first edition is worth a lot of money. I told a friend of mine this, who was a children's librarian, and she said she had all three books - signed first editions. She sold them at auction for a lot of much needed cash and then went into a bookshop to order a set of hardbacks to replace them. The assistant told her kindly that she didn't need to spend all that money on hardbacks as they were now available as paperbacks.

So take a look on your bookshelves. You never know!

2 comments:

Thanks for reminding me of these titles and cheering to hear of your librarian's Pullman hardbacks 'reward'.

And how different all these books were in tone and, with the Spyglass, in length.

Sometimes, especially now, I wonder if there is a link between the move to a topic-based curriculum (incl PSHE) and the rise of issue books?

Or was it, back then, boredom with the existing class sets of novels? Or the need for shorter texts that would fit into a half-term? Don't know. Just musing.

It would be interesting to know how big the market is for those class sets of novels. I have almost no recollection of reading remotely contemporary children's/YA fiction in the classroom - with one notable exception. In my first year at Grammar School we were given Alan Garner's The Weirdstone of Brisingamen to read and that, I suspect, was the end of my Enid Blyton phase. (I was 10). As for shorter texts fitting in to half a term, when I was at university I took a half-seminar entitled Proust, Joyce and Mann. We had the four week easter vacation to read as much as we could of A la Recherche du Temps Perdu, Ulysses and Mann's Buddenbrooks and The Magic Mountain!

Post a Comment