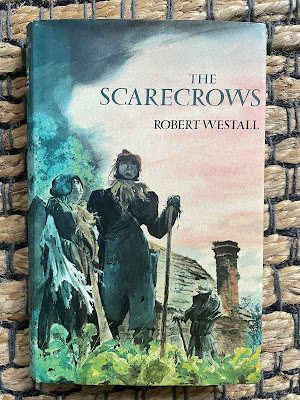

The Scarecrows by Robert Westall is a novel about sex, violence and masculinity. It won the Carnegie Medal in 1981 and it is very different from Westall's first winner, The Machine Gunners. It has taken me some time, and two readings, to figure out what is going on in the book: I started by feeling revolted by much of it, but while it's never going to be an easy read I have gradually realized that this complex story ventures into areas not often explored by fiction, whether intended for adults or children, and that the things that I disliked so much are there for a reason. Do I like the book now? No. Is there a lot to think about? Yes.

The book left a nasty taste in my mouth and despite many passages of very powerful writing, I don't think it achieves what it seems to be trying to achieve. It paints a vivid picture of a boy with a lot of problems who is in a difficult situation, but I can't see how it would help a child in the same kind of trouble. And, perhaps more importantly, I didn't think it was very scary.

The story is told from the point-of-view of Simon. He is in his final year at a preparatory school, from where he is destined to go on to Wellington College, a Public School with strong military connections. Simon is a deeply disturbed boy. His father, a professional soldier, has been killed seven years before the story begins, fighting for the British army in Aden. Simon's younger sister, Jane, was born after their father's death. Simon's mother works in an art gallery and is the source of huge embarrassment to Simon, who is one of the least sympathetic protagonists of any book I've read, running Ivan Southall's Josh a close second.

The book's opening chapter provides a supremely unedifying snapshot of life in a boarding school dormitory. Bowden, the chief bully, specialises in smutty innuendo about other boys' mothers, and in vile anti-semitism. In flashback we learn that, during the previous year's Parents' Day, Simon's mother has embarrassed him by agreeing to play in a tennis match. Rather than being proud that his mum is a brilliant tennis player, Simon hates the fact that you can see her bottom when she bends to pick up a ball. But then, Simon knows how the other boys will see things. The taunting in the dormitory that night -'I think your mother took service rather well' ... 'She certainly knows how to handle a pair of balls', lets loose what Simon thinks of as the devils in his head. He loses control and beats Bowden to a pulp.

As the story begins Bowden is at it again, though he no longer picks on Simon. He's scared of him. It's the evening before the next annual Parents' Day and Simon is dreading it. The reality turns out to be far worse than he could have imagined. His mum turns up in a white Range Rover with a man, and Joe Moreton is, in Simon's snobbish eyes, 'a yob'. He has no tie. He smirks and he leers and he smells of Gauloises. Worse, he is rich and successful. He draws political cartoons 'in The Observer and Private Eye', and, as we soon find out, he is going to marry Simon's mum.

Simon is the step-child from hell. Actually, he might be the child from hell. Because Simon idolised his dead father and sees his mother as betraying his dad with a man who couldn't be more different, a man who his mother actually loves, and who his little sister loves too. And they are all disgustingly physically affectionate with each other. One of the things I found hard to take when I first read the book was the way seven-year-old Jane is described as 'sexy', but I think this is because that's the way Simon sees her. Simon is filled with jealousy and obsessed with sex. He is disgusted and, as we discover, pruriently curious at the same time. I should add that I didn't find Jane a very believable seven-year-old, and I've met a lot of seven-year-old girls. That's the kind of false note that makes it hard to suspend disbelief in a story, and if you're going to believe in the evil scarecrows you really do need to believe in the more everyday characters.

At first I thought there was no humour in The Scarecrows, but that's not true. There is humour but it's a bitter, sarcastic humour. In fact, it the humour of the professional caricaturist—the humour of Joe Moreton—what Simon thinks of as 'the strange and hateful talent of Joe Moreton'. We first see this talent at the Parents' Day, where Joe is asked to draw a cartoon of the Headmaster to auction for the school funds.

'But slowly, out of the slashed scribbles, an image of the Head emerged. Bald head, spindle shanks, paunchy tum under grey waistcoat. The drawing made him look tiny, like an aggressive robin. So real you had to laugh. Except Moreton showed more than was there: the tension in the clenched hand on the wing of the car; the Head's desperation under the politeness he always showed to rude bullying parents. Moreton stripped the Head naked.'

When Simon goes to Joe's exhibition at the gallery where Mum works he realizes: 'All Joe Moreton's people looked scared underneath.' Joe's drawings are funny, but devastating and cruel, and the 'comic' characters in this book might have been drawn by Joe. There is Mercyfull, the repulsive old gardener who is as much of a snob as Simon about the upstart imposter Joe Moreton. There's Cosima in the village store who delights in crying out that she feels as if she's been 'raped' when the press descend on her shop (the whole section about the national press descending on the village to try to preserve the old mill seems completely unnecessary to me), and there's Mrs Meegan, the woman who works for Joe as an artist's model, with her sagging breasts and painted face. Simon tries to see what's going on in the studio by climbing a tree and, when Joe spots him, Simon refuses to get down. Joe sends Mrs Meegan away and takes his revenge by drawing Simon. Simon is outraged and when he and Mum enter the studio the drawing is pinned to the wall:

'A hunched little figure of pure hate . . .

"That's not me. It's not, it's not, it's not!"

All the adults burst out laughing.

"The spitting image," said Mrs Meegan.'

But that's not the worst of it. When Simon rips the drawing to pieces Joe calmly starts drawing again. The drawing will never go away. Joe can recreate it any time he wants. 'If it's a lie,' said Joe, 'it won't hurt him. Lies don't hurt. And if it's the truth, it's about time he knew it.'

And then there are the scarecrows. You might think of them as the ultimate caricatures. Oddly, despite their title role, they don't show up for 100 pages. There is an old watermill near Joe Morton's house, on the other side of a turnip field. The mill is haunted by the ghosts of 'the young miller', his wife, and the wife's lover, whose name is Starkey. Starkey and the miller's wife murdered the miller, and were later executed for the crime. When Simon enters the mill it appears to be just as it was left on February 1, 1943, the date on a newspaper on the table. (WW2 is never far away with Robert Westall). But Simon summons their spirits and they appear later in the field as a trio of scarecrows who move slowly and threateningly closer to Joe Morton's house as the days pass.

I've spent a lot of time thinking about those scarecrows—about who and what they represent—and I'm still not entirely sure. Westall says somewhere that he uses the supernatural to symbolise what's happening inside his characters. When Simon pushes over two of the scarecrows they appear to fall into a sexual embrace, echoing the 'animal noises' that Simon has heard from his mum and Joe when he's been eavesdropping on them having sex (and, almost more excruciatingly, talking about him.) The third scarecrow, the really scary one who Simon thinks of as Starkey, is surely Simon himself. and Starkey is about to kill.

'He turned on the third scarecrow; advanced. But he still couldn't read the third scarecrow's look. The third scarecrow was far, far worse. The third scarecrow looked like he might fight back . . .'

So when Simon gets out his father's loaded revolver it does seem entirely possible that he might kill someone. We already know from Simon's eavesdropping that his mum's relationship with his father was deeply unsatisfactory, both emotionally and sexually. We already know that she thinks Simon is hard inside, just like his dad. But it's still shocking when she says, after the incident with the gun:

"'I saw you born; I saw you come out of my body. But I swear . . . you're no part of me. You're all Wood, Wood, Wood. You're just another one of a long line of . . .'

But it wasn't what she said. Its was the way she said it."

Even if you're angry it's an odd thing to say to a distressed 13-year-old. I think I've said enough to show that this is a very grim book indeed, and it feels at times more like a warning than a novel—a warning about how not to bring up a child. What's more I haven't managed to understand the ending, no matter how many times I've read it. It seems as if the scarecrows are about to kill Simon and his family and that Simon finally banishes them when he thinks happy thoughts of Mum, Jane, and, almost, of Joe, but I wasn't at all clear what it was that the scarecrows were about to do. I am reminded of Philippa Pearce's (unjustified) criticism of The Owl Service that it failed to 'make plain' what was happening. The thing about The Owl Service— which must surely have been an important influence on this book, dealing as it did with social class and step-families and with its supernatural scaffolding— is that, in its own terms, it makes sense. I'm not sure that The Scarecrows does.

Nor does it provide a great deal of hope. Westall says that a question he asks himself is 'How do I tell them the truth without destroying hope?' Is there hope for Simon? Simon has heard and seen a bit too much truth in this book, if you ask me. He has heard his mum tell Joe what she thinks his future will be; away at school, then into the army, coming to see her twice a year 'out of duty'. She thinks they'll be better off just the three of them, her and Joe and Jane. No Simon. He's heard her describe sex with his dad: ' . . . he just took me, like I was another fence, another parachute jump. Then he turned his back afterwards and lay and smoked in the dark. I could never touch him . . . ' And he's seen how Joe has seen through him. It's meant to help, isn't it, seeing yourself as others see you? But I don't think it helps Simon. When he thinks the scarecrows might kill Joe he thinks: 'Joe had a right to live too. Not, maybe, a right to Mum, Jane, Tris. But a right to live.' Hope is doled out in very small portions here.

As has often been the case with this Carnegie reading project, one book has led to another. Robert Westall was undoubtedly one of the most important writers for children and young adults in the latter years of the twentieth century, and not all of his books are as grim as The Scarecrows. I also think that many of them are better than The Scarecrows. For an excellent survey of Westall's work I'd recommend Westall's kingdom, an article by Peter Holindale in Children's Literature in Education Vol 25 Issue 3, 1994. It's available online and is behind a paywall but if you're in an academic institution or somewhere like the British Library you can access it there. In the meantime I have some recommendations. Firstly there is the excellent collection of autobiographical pieces in The Making of Me. This book is mainly about childhood and schooldays, and there's a fascinating piece at the end about The Machine Gunners and Westall's editor, Marni Hodgkin.

My second recommendation is the short novel Gulf, published in 1992 and shortlisted for the Carnegie that year. In this book Westall blends realism and the supernatural (or perhaps inexplicable is a better word) seamlessly. Tom, the narrator, has a little brother who he calls Figgis because, before his brother was born he had an imaginary friend called Figgis. Figgis turns out to have a gift for what might be called extreme empathy, and when the Gulf War breaks out he enters the mind of a boy soldier in Saddam Hussein's army. This brilliant novel incorporates ideas from much of Westall's earlier work into a taut, moving and entirely convincing story which has lost none of its relevance today.

And then there is The Kingdom by the Sea. This novel about a 12-year-old boy who survives the bombing of his house on Tyneside in WW2 and takes off on a journey up the Northumberland coast is as life-affirming as The Scarecrows is not. Published in 1990 it won the Guardian Children's Fiction Award and was commended for the Carnegie. I'm not sure it's a children's book, any more than is Claire Keegan's Foster, which I read recently and which has some parallels with Westall's book, but it is definitely wonderful.

Finally, you might like to know that in 1981, the year of The Scarecrows, Jane Gardam's The Hollow Land was highly commended for the Carnegie, and her Bridget and William, as I mentioned last month, was also commended, as was Michelle Magorian's Goodnight Mr Tom. I'd say that either of the Jane Gardam books would have been more worthy winners than The Scarecrows, and Goodnight Mr Tom doesn't seem to have suffered too much from not being selected either.

In my brief search for other sex-obsessed adolescents to rival Simon as unsympathetic protagonists I pulled Alan Garner's Red Shift from the shelf. I felt devastated for all three of the couples whose stories are told across time, but especially for the modern day couple, Tom and Jan. Tom is a tortured character, and he's made a mess of things, but I can relate to his misery in a way that I can't to Simon's. It's baffling to me that Red Shift wasn't even on the shortlist in 1973 when a few years later they were prepared to give the award to a far lesser book in The Scarecrows. Mind you, two of the commended titles in 1973 were Nina Bawden's Carries's War and Susan Cooper's The Dark is Rising, so 1973 was a pretty good year.

And, in case you've missed the news, there is a new radio dramatisation of The Dark is Rising by Robert Macfarlane coming to the BBC in December. Now that is something to look forward to!

No comments:

Post a Comment