Within a few months, a series of incidents occur and coincide which have made this series of interviews not just possible but entirely synchronititous. Firstly John Garth follows up his acclaimed book on Tolkien in the Second World War, with a book which explores the landscape of Middle Earth and how Tolkien created and built it. Then, quite unexpectedly, I find myself back in Narnia after finding out about Kath Langrish's forthcoming book 'From Spare Oom to War Drobe :Travels in Narnia with my nine-year-old self.'

For a long time I have also always wanted to interview Brian Sibley because - amongst many other things to be proud of - he was one of those responsible for the first and entirely wonderful, radio dramatisation of The Lord of the Rings in 1981. Brian kindly provides me with a whole world of wonder and memories during Part One of our interview. Only afterwards do I realise that that first broadcast was on Sunday March 8th 1981.

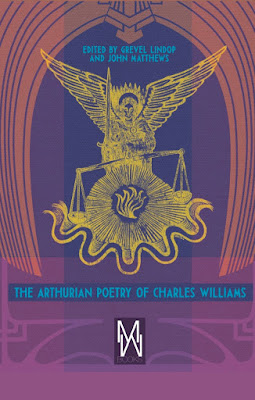

That leaves Charles Williams, the third of the Inklings and too often forgotten in the wake of the success of his friends C.S. Lewis and Tolkien. I've always meant to read him, but as so often occurs, have never grabbed the opportunity. Luckily in March I am interviewing my friend John Matthews, who immediately introduces me to Grevel Lindop, whose 2017 biography of Williams 'The Third Inkling' was widely acclaimed. John's own interview included a quick 'coming soon' for Grevel, with whom he collaborated on the last edition of Charles Williams's Arthurian Poems.

I'm delighted to be talking to Kath, Brian and John Garth in the next couple of months, but it's a pleasure to begin with Grevel.

Grevel, First of all thank you very much for agreeing to talk to us at 'An Awfully Big Blog Adventure', and starting the ball rolling on this series of interviews about the Inklings.

It's a pleasure. Thank you for the invitation.

You were introduced to me a few weeks ago by our mutual friend John Matthews, who knew I needed to talk to someone about Charles Williams. Having written a recent biography about him, 'The Third Inkling', it was clear you were the ideal person to talk to. What I didn't expect was that my taking a crash course in Charles Williams, would end up being such a wonderful and unexpectedly enriching experience. I had only ever heard of Charles Williams in relation to his two more famous friends, J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis, but - to coin a phrase - I really had been missing out. Why is that?

You're not alone, Steve. Charles Williams has been very much overlooked. As we might discuss later, he fell into neglect partly through an accident of timing. But also his work doesn't easily fall into any of the categories by which literature is marketed. His novels - they might be called 'spiritual thrillers' - cross genres between action thriller and fantasy. They're not like any other books; they're hard to place. And his poetry, though great, is also often obscure. I'm sure we'll come back to those topics later.

Now Charles Williams- as John has already expressed in last month's interview - was an extraordinary man by any standards. His sight was severely compromised so that he had no distance viewing, he had a permanent shake, and decidedly humble beginnings. All that has to be impressive on its own, don't you think - considering what he achieved and how much of it?

In a way, yes. Williams came from a very poor family, was largely self-educated, and worked his way up via a humble job in publishing and also as an evening class lecturer, to become a well-known author, playwright and broadcaster, and a hugely influential lecturer at Oxford University. He was also an important figure in the worlds of both occultism and mainstream Church of England. He was fascinating, charming and charismatic, and after his relatively early death, (at 58), he left disciples. I met many of them and they all said he had changed their lives profoundly for the better.

Grevel, exploring your highly varied life and enthusiasms via your website, I was struck just how recently your biography of Charles Williams came in comparison to everything else - after your work on Thomas De Quincey for example, and your salsa tour of Central America for example! Would I be right in thinking that yours is an enthusiasm that goes back much farther than that? Perhaps you could sketch in for us how he fits into the rest of your life and career?

Charles Williams was recommended to me back in the 1970's by my Buddhist meditation teacher - who was himself something of a magician. So I read Williams's novels, which I loved, and some of his poetry - which I found difficult but fascinating. I came back to Williams from time to time, (being also a big fan of Tolkien, Lewis, and the Inkling philosopher, Owen Barfield - an important thinker who is still shamefully overlooked); and I went deeper into him when I briefly taught a 'Special Subject' course on the 'Inklings' at Manchester University in the 1990's. I've been interested in occult fiction - I started Dennis Wheatley as a teenager in the 1960's.

I quite understand, Grevel. I was doing the same thing a decade later!

I'm also keen on the novels of Dion Fortune, who like Williams had a background in the Order of the Golden Dawn.

But the deciding factor was when the magazine PN Review sent me to interview the poet Anne Ridler in the early 1990's, and I discovered that she had been mentored by Charles Williams. She had a wealth of memories of him, and also many of his letters. I realised that there was just time to gather material for a life on this amazing man, before those who had known him were gone. He was about to go over the horizon of memory, you might say. So I began interviewing everyone I could find who had known him. And I went on from there.

T

| |

| The poet Anne Ridler - who helped to modernise CW's poetry |

And yet, here we are, about to enthusiatically discuss Charles Williams and his quite incredible poetry and novels, and yet he gets left outside in the cold in the wake of his friends Lewis and Tolkien. He seems to have been a very modest man, but he certainly was by no means short of contacts through his work for Oxford University Press. He was clearly revered in his own time, so what did happen to his reputation when he died?

Partly, it was unlucky timing. Williams died during the last days of World War two: news of his death and assessment of his work, were swamped by more important global matters. Second, the war left a paper shortage, and his books went out of print. Thirdly, his marriage had been difficult; his widow had no idea of how to market his books, she didn't get on with his 'disciples', and she wouldn't allow a biography because it would have turned up uncomfortable facts. So many of the avenues to discussion of a recently- deceased author were closed off. New readers couldn't discover him.

One of the many interesting things about Charles Williams was that when he talked and wrote about magic and the spiritual world, he really did know what he was talking about because he was there at a time of a great flowering of English Magic and spiritual matters. This is abundantly clear in many of his novels, where - as John has previously stated - he describes ritual and the objects used from an insider's point of view. He really does know what he's talking about.

Exactly. Through his publishing work he got to know A. E. Waite in 1917, and joined Waite's 'Fellowship of the Rosy Cross', a mystical Rosicrucian Order. But he also came to know D.H.A. Nicholson and A.H.E. Lee, both of them 'Golden Dawn' initiates who were still running a small branch of 'Stella Matutina', the magical order that survived from the original 'Golden Dawn'. So as well as being a committed Christian, Charles Williams was an initiate of two occult groups. The FRC was more contemplative and mystical: the SM aimed at more practical magic. So he knew a bit about both, and could introduce both magical and mystical material into his fiction with an insider's knowledge.

|

| Camelot |

Being already a great enthusiast of the poetry of Taliesin, and his mythical connection with King Arthur and the Arthurian stories, I found it easier than most to cope with some of the incredibly complex poetry in Charles Williams's two most famous cycles, 'Taliessin in Logres' and 'The Region of the Summer Stars'. The novels are much easier - if both religious and spiritual in fairly equal measure. But truly, the two books I've read - 'War in Heaven'- his Grail novel, and especially 'All Hallows Eve' - which has an incredible and often dark power - well its true that you'll never read anything like them. Yes, there one or two bits that don't work, or else are a bit overblown, but you forgive that because they are incredibly powerful.

I think it's partly that they start from the everyday world. And although they deal with spirtual matters, they don't assume that either the characters or the reader are either 'spiritual' or 'religious'. Williams understood that most people didn't see themselves as religious, and so he draws you in gradually by means of mystery and suspense, amd allows the weirdly powerful occult and mystical elements to unfold stage by stage. You don't have to accept some fantasy world in order to read a Williams novel. He shows you that the strangeness and weirdness are all around us in daily life.

And yet, Grevel, he clearly had a strong faith. Like his friend Lewis he later became famous for his religious writings - and like Tolkien - a practicing Catholic since birth, it was something which completely shaped his life. You can't really read the novels, can you, without being constantly aware of his faith and where's he coming from, even if he doesn't hammer it home all the time?

As I say, the 'faith' - I would rather call it a world-view actually, because it's completely matter-of-fact and down-to-earth, despite its strangeness - is there throughout; the characters discover it in the course of the story, and so does the reader.

|

| CW in the snow outside Southfiled House, Oxford - the war-time headquarters of OUP. |

Your book, 'The Third Inkling' begins quite wonderfully when Charles Williams - in many ways an unimpressive figure, tall and stooping and bespectacled- is escorted on to the lecture platform, with his friends Tolkien and Lewis on either side of him. There isn't a large audience, or initially at least, any particular enthusiasm. And then he begins to speak and his pretty strong working class London accent emerges, so strong and alien to his audience. You also describe how years later at his first lecture in Oxford in the first year of the war, a few of the audience, used only to a well-spoken Oxbridge kind of English, immediately turn off and wait for the lecture to end. But Williams has the last laugh in both cases, doesn't he?

He does, because although repelled at first by this very harsh London-Hertfordshire accent, after a few moments people were charmed, fascinated, even hypnotised by his intelligence and the brilliant perceptivness of what he had to say. I mentioned in the book that he was probably the only person who maintained equally close friendships with T.S.Eliot and C.S. Lewis - who couldn't stand each other. They both loved his company. Lewis thought he was a great man. Eliot thought he was possibly a saint. In that context, the rough accent was forgotten!

Charles Williams produced several poetry collections, but the two which gave him his reputation were the two Arthurian collections; the first - much longer - collection 'Taliessin Through Logres', and the later, pamplet-sized collection of eight further poems in the sequence, 'The Region of the Summer Stars'. Now we've already heard from John Matthews about the ancient Welsh bard Taliesin, (CW always spelt it with an additional 's'), but it's probably fair to say that Taliesin is a pretty obscure figure who you might not have heard of unless you delve fairly deeply into Welsh myth. How might Williams have discovered him?

I'm sure Williams first found Taliessin in Alfred Lord Tennyson's, 'Idylls of the King', his Victorian sequence of Arthurian poems.. Indeed it is Tennyson's spelling, with the two 'S', that Williams follows. But then from a very early age he was planning an Arthurian epic, and he read everything he could find on the subject, including Malory and the Mabinogion, in Lady Charlotte Guest's translation.

In the collection of Charles Williams's Arthurian poems on which you and John collaborated, you carefully prepare the reader for the odd complexity of the poetry and some of the themes and ways of reading them. They feel to me rather like a forest - just when you see a familiar landmark, you get pulled off on another route.

That's right. In that respect, it's a bit like reading 'The White Goddess' by Robert Graves. When I edited that book, I also compared it to an 'enchanted forest'. The key to reading books like those is NOT to try to understand them at first reading. Just let them flow through you like a dream. Don't try to make sense of everything. Let the magic do its work! As you come back and read again, which you also need to do from time to time, bits and pieces will fall into place. It will make more and more sense. But you have to let the unconscious do its work. These writings are addressed to deep levels of the mind, which don't operate with the same logic as the surface thinking we are used to.

We cannot talk about Charles Williams's life without bringing up the many women in his life, and their influence. Leaving aside the several instances of a mild level of sado-masochism with several of his muses, he appears to have been someone who inspired great loyalty - and in many cases love - from the women who knew him. His books and poetry would have been completely different had he not known, learned from and in many cases collaborated with those women, don't you think?

Definitely. Like Graves, Yeats and many other famous poets, he needed a female 'Muse' to fire up his deespest creativity. I met - I think - five of his 'Muses'; all of them appear as characters in his poems at various points. All of them challenged them, debated with them, and in some cases went over his poems and helped edit them. Anne Ridler in particular, as a young Modernist, helped him to find the new style which made his Taliessin poems so successful. She would go over his poems word by word and criticise them; and he had the good sense to listen to her.

|

| Chief among Charles Williams's many muses - Phyllis Jones |

What about his place as a poet in the twentieth century? Where do you think he stands amongst his other and more famous colleagues like T.S.Eliot, W.H. Auden and Dylan Thomas?

He's not as great as Eliot, (though Eliot did confess he got that bit about 'the still point of the turning world' from Williams's novel 'The Greater Trumps'. He's not as readable as Auden. On the other hand many of Dylan Thomas's poems are even more obscure than Williams's. I think he will always be something of a minority taste; but those who discover him and love him will keep coming back. He is certainly - as Lewis said - the greatest Arthurian poet of the twentieth century.

Finally, Grevel, having had such a long enthusiasm for Charles Williams, there must be questions you'd like to ask him, were he around to answer them. If you had the chance to meet him, what would they be?

All sorts of things! I'd like to ask him if, as a prominent reviewer of crime fiction, he ever met Agatha Christie; and if so, whether he agrees with me that she probably based the composer 'The Mysterious Mr Quinn', on Williams. More seriously I'd like to ask him to tell me about the novel he planned to write, but never did, based entirely on the world of the dead. And is it true, (as one of his poems seems to say), that he once lifted his disciple Anne Scott on to the altar of St Cross Church in Oxford? I half believe he did, but would love to know. But would he tell me?

I guess those three questions give some idea of the strangeness of Williams - and his life. I hope they'll whet people's appetite to know more.

I do hope they will, and you've certainly done your bit this month to encourage them. Many thanks, Grevel.

Many thanks to you, Steve, for asking me.

Finally, and most importantly, there follow links to both Grevel's website, and to easy purchase of his book 'The Third Inkling', which I will say again, is an excelellent and at times compelling read.

Website first

www.grevel.co.uk

Copies of 'The Third Inkling' are available from Amazon

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Charles-Williams-Inkling-Grevel-Lindop/dp/0198806434/ref=sr_1_1?crid=RG0EZNTUV1CB&dchild=1&keywords=grevel+lindop&qid=1618149056&sprefix=Grevel%2Caps%2C151&sr=8-1

It's

been a pleasure to begin my summer with the Inklings. On Friday, in my

regular slot, I will be burrowing back through the wardrobe into Narnia

with Kath Langrish. See you then!

3 comments:

Thsnk you, Steve, for a full and worthwhile interview. Fascinating!

ps. I particularly liked the phrase "the horizon of memory" as used in:

"I realised that there was just time to gather material for a life on this amazing man, before those who had known him were gone. He was about to go over the horizon of memory, you might say. "

Post a Comment