While I've been reading Carnegie Medal winning books I've found this question popping into my head occasionally. Usually I think about it while I'm digging on the allotment and then decide it's not worth writing about. Or rather, I decide that it's too complicated to write about and I'm not really sure what I think.

|

| The allotment. Plenty of digging, plenty of thinking |

But in the past few weeks I've read a series of historical novels and one non-fiction history book, and that question has kept nagging at me because the books I've read range from one which is definitely written for children to one which, although marketed to children, seems to me to deal with themes which are almost exclusively adult.

I suppose the first thing to say is that, speaking (as Noel Streatfeild might have said) as a children's author, all my own books have been written for children, and the subject-matter, style and vocabulary have been carefully adapted to my target audience. To be sure, I always hoped that adults would read at least some of those books too, and not only professionals like teachers and librarians and maybe even reviewers, but parents too, and friends and family. But, in the end, my children's books are written for children.

A Valley Grows Up by Edward Osmond won the Carnegie in 1953, the year I was born. Osmond was a teacher and artist who was encouraged by a children's editor at OUP to turn his idea for a series of wall-charts depicting an imaginary valley at various points in history into an illustrated book. His paintings had originated as blackboard drawings used to teach students after World War II. No question then that this is a children's book. Like many early winners it has a definite 'teachery' feel to it in the voice of the author. Given its origin as a series of talks based on a series of paintings this is not surprising, and it is the voice of an interesting teacher. It's also the voice of a man with his own prejudices which he makes no attempt to conceal. The earliest 'real men' to come and live in the valley are described as 'grotesque and primitive' and in the 17th Century the 'Roundheads' get a very bad press. After successfully attacking the castle 'the Roundhead army moved on to other acts of destruction elsewhere . . . During the dull years of the Commonwealth, after King Charles had been captured and executed, few changes were made because there was no feeling of enterprise in the country.'

The book is a curious mixture of fact and fiction. Osmond describes events in his imaginary valley as though they really happened, which does feel confusing at times. I was a little surprised at the poor quality of the reproductions in my copy of the book, and I wondered if I had a duff one, but then I found this from Marcus Crouch: 'It was unfortunate, if inevitable, that in reproduction the original pictures lost much of their definition and their detail. The reader sometimes looks in vain for a feature mentioned in the text but reduced into invisibility by the block-maker.' I find this very odd as my copy has an ad on the back flap for The Map That Came to Life by H J Deverson and Ronald Lampitt. You can see this wonderful book in full online and the illustrations are beautifully clear.

|

| A spread from The Map That Came to Life |

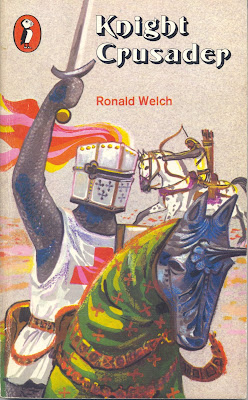

In 1954 the Carnegie was won by a very different kind of history book - Knight Crusader by Ronald Welch. If you did not know that Ronald Welch (real name Ronald Oliver Felton) had seen service during WWII (in the Royal Welch Fusiliers, from whom he took his pen-name) and then become headmaster of a boys Grammar School, I think you could have guessed. This is a book in which the protagonist is a boy on the threshold of manhood. What kind of a boy? This kind:

'The robber flung up his arm helplessly, his face a mask of fear and snarling fury. But there was nothing he could do to ward off this thunderbolt of sudden death that had swept upon him. He went down with a strangled scream as Philip's sword caught him full across his turban, and split his skull with a sound like that of a hammer smashing down on a length of thin planking.'

There is a LOT of fighting, some tournaments (where people get seriously hurt), a couple of major battles, and a siege of a Welsh castle. The body count could rival that of a modern Hollywood action movie. The story is set in the Crusader realm of Outremer in the late 12th century, and place and time are brought vividly to life, but the characters are more than a little two-dimensional. The first female character makes her appearance on page 234. Here she is:

'Philip [sat] with the Lady de Clare on his other side. She was a dark-haired, imperious-looking woman, most magnificently dressed, and by her manner fully conscious of her position as the leading lady of the Marches.' (That's all you see of her.)

The second woman appears just a few pages later: 'The Lady Anne de Chaworth was a tall, spare lady with a determined chin and a rasping voice. Her eyes missed nothing as she watched her servants, and even her mournful husband obeyed her instructions with a meekness that made Philip smile. Perhaps this explained Sir Geoffrey's gloom, he thought.' (That's more or less it for her, too.)

And there you have the whole female presence in the book, apart from a short scene where a gruff old soldier teases a couple of children, one of them a girl (the only real children in the book). This is, essentially, a book about men fighting and killing each other in a meticulously researched and realised 12th century world, and yet it is distinctly NOT a book for adults. No women or children to speak of, a bunch of men fighting and killing each other, and yet it's a children's book. 'For readers of eleven and over.' says my Puffin edition.

|

| Illustration by William Stobbs |

I know just who this book was written for. It was aimed squarely at Ronald Welch's grammar school boys and I'm sure many of them loved it because it's rather like an extended version of a war story in a boy's annual of the period. What character development there is consists in the protagonist getting better at fighting. But, given that this is a book entirely about adult men I had to wonder what was missing that would have turned it into a novel for adults. The quality of the writing is better than that found in many thrillers: perhaps a star-crossed romance woven into the story would have done the trick? Character development is not essential to an adult novel either though - look at Jack Reacher or James Bond. Is it just that the book doesn't have enough to say to its readers? Is it not subtle or complex enough to be marketed to adults? Is it, perhaps, a little childish in its simple, gung-ho revelling in violence; childish in a way that The Borrowers, for example, is not.

You will have to forgive the randomness of these thoughts. I'm hoping that by writing them down they might become clearer. My next random thought is that maybe children's books about adults are acceptable when they are distanced, either by history or fantasy or maybe by space. The Hobbit, for example, is about a group of fairly elderly dwarves and an adult hobbit on an often violent and dangerous quest. The Wind in the Willows may be about animals, but it's about adult animals with their own homes and lives. I'm struggling to think of a realistic children's novel with a contemporary setting that is entirely about adults.

|

| Cover by Charles Keeping |

And so to Rosemary Sutcliff. I'm leaping ahead in the Carnegie winners list to 1959, and I want to write more about Sutcliff later, but The Lantern Bearers, which was the 1959 winner, is a book about adults in which the chief themes concern the struggles of the central character, Aquila, to come to terms with the savage murder of his family, the kidnapping and probable rape of his sister, and his own problematic relationship with his son and wife. The bleakness of Aquila's despair after he finds his sister (after several years as a slave himself) married to a Saxon and with her own child and a new life is brilliantly portrayed as a kind of bereavement and a betrayal. I really can't think of any reason to call this a children's book, other than that it was published and marketed as a children's book, oh, and it has pictures - wonderful illustrations by Charles Keeping which make this one of the most beautifully produced books I know.

|

| Spread by Charles Keeping |

It's interesting to compare The Lantern Bearers with its sequel Sword at Sunset which was published for adults in 1963. I haven't finished this yet, but there are already some obvious differences. The story is told in the first person by Artos, who we know as King Arthur. It is wordier than its predecessors, there is a sex scene early in the book and there are no pictures. There are also many long paragraphs unbroken by dialogue. And the stylistic devices that occasionally irritated me in Sutcliff's 'children's books' are even more in evidence here - notably her tendency to make characters speak in a slightly stagey archaic manner, especially if they are 'tribal'.

And so my thoughts circle back to the place they always end up when I'm out there digging. Do I really need to know what a children's book is? I'm not so sure I even know what a child is. I suppose the bottom line is that I wouldn't want any child not to read an 'adult' book simply because it was not written or published for children, and I wouldn't want an adult reader to miss out, say, on The Lantern Bearers for the same reason.

I believe - I know - that it is possible to write for children in simple language and still tell a story that is rich and complex, and to do so without talking down to the children; without sounding like a teacher or a dotty old uncle. I thought that kind of thing was disappearing from the Carnegie winners until I reached C S Lewis (1956). I have plenty to say about him, but before that we have Eleanor Farjeon (1955) who occasionally wrote stories that defy any kind of categorisation and who definitely deserves a whole post to herself.

All of Ronald Welch's historical novels about the Crecy family are in print, with the original William Stobbs illustrations, available from Slightly Foxed magazine. Hazel Wood found more to like in Knight Crusader than I did, and her piece in Slightly Foxed magazine (No 39) will tell you why, and why she was inspired to republish the books. Slightly Foxed also have their own edition of the Rosemary Sutcliff Roman books with the Keeping illustrations, but for my money you can't beat the original OUP ones if you can find them.

4 comments:

Thanks again, for your post. The fuzziness of the "About a Valley" illustrations did puzzle me too. I wonder if the hazy effect was in any way linked to his original use of chalk on blackboard? And maybe nobody proof-read the text in relation to the eventual art work?

Titles like these seem to be very much about re-defining the history of England/Britain after the devastation and personal cost of the war: "We have been through times of violence and loss before, my friends, and we survived to tell these tales." Just pondering on.

I agree, Penny. WWII cast a very long shadow over children's literature and I'm not sure we're done with it even now.

Excellent post, Paul! Fascinating stuff (and re your comment, I don't think our current PM has done with WWII yet either! Maybe he was brought up with the books you mention!)

I'd agree, Paul. Sadly, I feel the last spate of war anniversary films and novels may have fed into the Referendum decision. Wish I didn't.

Post a Comment