I am currently spending a lot of time Head Writing a new 52 episode adaptation of The Wind in the Willows. It's been a long time coming, I began working on it back in 2018 and now it's finally gone into production. I love the book, I love the characters and it's been a joy to dive into a simpler world after all the chaos of the last year or so.

That's not to say literary adaptations are easy - they're tricky beasts - and The Wind in the Willows has it's fair share of Toad size mishaps to blunder into if you're not careful - poop poop and all that.

You want to remain true to the original material while making sure it stays relevant for a modern audience - that's true of everything, but is especially tricky if your source material was first published in 1908. A fair bit has changed and you need to modernise the material - or at least the relationships within it - without riding rough shod over the things that make it classic.

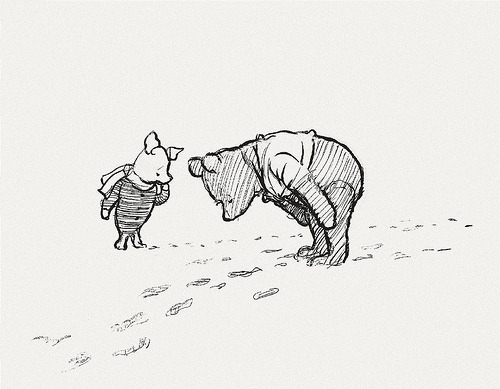

The Wind in the Willows has a few tricky bits and pieces to negotiate. One of the main problems is that the core trio of Toad, Ratty and Mole are all male - so too are many of the incidental characters. That had to change. We toyed with changing the gender of Ratty, but in the end plumped for introducing a new character into the centre of our core characters - Hedge, a feisty young hedgehog who can give the boys a run for their money. How could you not love that face?

'Sacrilege,' I hear you cry! But to be honest, you're damned if you do and damned if you don't. Change a gender of a core character - wokeism. Add a new character - meddling with a classic. Like I say, adaptations are tricky beasts, I have a feeling we've done the right thing.

The class structure is also fairly alien to our young audience - or maybe not. Having a buffoon like Toad mucking things up for everybody might ring some bells for the rest of us... Regardless, there is an underlying metaphor about class struggle embedded in the book, with the filthy proletariat weasels from the Wild Wood rising up against the bastion of all that Toad Hall with it's manicured and ordered gardens represents. We've had to tone that down. We've also toned down some of the mysticism - sorry.

We've had to tone down Toad too. He's a great character and will take over every story if you let him. In the days of ensemble storytelling we want each of our main characters to have a place in the series - this isn't the Toad show. I liken it to Last of the Summer Wine. The three characters at the heart of that series are not unlike Ratty, Toad and Mole. They each have their flaws and their strengths and you want to give them all stories worth telling.

We've also been colour blind in casting the voice talent to make sure our Wind in the Willows reflects the society we now live in. Like I say, a lot has changed in 110 years. The problem with all of this is you're always conscious of the uproar The Daily Mail will try to make of everything. But I'll be honest, given they'll make an uproar over how you label a chicken these days, let them get on with it I guess.

But for all of that, there is a real joy in coming up with new stories for such well loved and well formed characters. Taking the book back to it's essence really gives me an appreciation for the craft of Kenneth Grahame. He balances the core trio beautifully, and at it's heart The Wind in the Willows is a surprisingly modern character comedy. It has an almost sitcom feel.

One of the advantages - or disadvantages depending on your point of view - of this adaptation is that Grahame isn't around to tell us if we're getting it right, or object if we're getting it wrong. Often when I do a literary adaptation the author - and sometimes illustrator - are in the room with us as we try to make a text meant for one medium fit another.

Most authors get stuck in. I had a great time with Alex T. Smith when we adapted Claude for Disney. Claire Freedman and Ben Court were there when we adapted Aliens Love Underpants which found a home on Sky. Ed Vere really helped when we adapted Fingers McGraw. Sometimes you don't meet the authors at all, as when we adapted Miffy and Pinkalicious.

I don't know if it helps being an author as well as a scriptwriter. Sometimes I feel like I'm poacher turned gamekeeper, but I also like to think I see both sides of the process. When you write a book you control everything that happens in the world, then suddenly it's being ripped apart and reassembled by hundreds of people in front of your eyes. It can be a very scary thing.

Like I say, tricky beasts literary adaptations.