A day or so ago, as I scrolled through book-related social media, my mind seized on a question shouting from the screen.

“How many books do you read in a month?”

How many books can I read in a month? I thought, the question already squatting on my worry list.

Oh help!

The night before, at my monthly book group, I was handed the single library copy of next month’s title, Lady of the English by Elizabeth Chadwick, to read pretty nippily and pass to others. I am interested in this historical novel - about Queen Matilda - but the need to speed-read 500 pages as soon as possible feels a very mixed blessing, as well the rush being slightly disrespectful of the author’s work. So, with my own worry in my head, I studied the question again.

The writer, in a particular group, was worried she might be falling behind in her reading. Surely the more books she read, the better, she seemed to feel? So, being nosy, I scrolled down through the group’s comments and could hardly believe the replies.

The number of ‘books read per month’ for some members rose into the teens, and even into the mid-twenties. Could these unknown bookworms really be reading a new novel every two or three days? Honestly, the rate seemed hardly credible.

What was it with these twelve, fifteen, eighteen, twenty-five books?

How did these particular readers even find the time?

And what was the reading culture that lay behind the pattern?

Then I realised that these enthusiastic over-readers could well be what keen teen readers become as they grow older. Some of them might even be teens still, and in school or college? How on earth did this frantic ‘more, more, more’ mood relate to children’s books and the practice of reading?

Several thoughts started going round in my old, trying-to-be-curious-and-please-not-too-judgmental mind.

Now I confess I am a greedy reader myself; starting as an early reader, I have always sped through pages too quickly, driven to know the plot. I do wish that I could read more slowly and enjoy the moment and the text better, as well as remembering more about the book when I’d got to the end. I know, myself, that faster reading is not, of itself, a good or admirable skill, no matter what merit it once had in school.

Was the reader's anxiety about the quantity of titles read the consequence of her education? Were her habits the result of years of those school reading schemes where answering chapter-questions indicates progress and approval, and got you the next tick, star and book in your book bag? Did this quick, credit-based system, which can now be done by children online from home, mould their reading experiences? Next, next, on to the next!

Then I wondered about the kinds of books that the grown-up speedy readers chose. They often seemed to be from a single known genre (such as contemporary psychological thrillers) rather than complex or different novels. There seemed to be an enthusiasm within the group for binge-reading series written by a favourite, familiar voice, which I can totally understand, as well as praise for certain authors who seemed to produce several novels a year.

Who? What? Where? How? Whatever? This bit of book world puzzlement is still to be solved!

Besides, it seemed that long and complex novels were not really their thing. Is ‘shorter and thinner’ where books are now, even for grown-up readers? I can’t remember names like Kate Atkinson or Hilary Mantel being suggested, or any older novelists. Maybe those older novels simply take too long to read and so lower the book score? Although not everyone has plenty of time, surely anyone naming twenty book titles a month might be interested in trying them out?

Gradually, I realised the group seemed to have a trans Atlantic audience, reminding me of question UK writers, for young or adult, often face: Will it sell in America? Or should that now be Is it short enough for the American market? I don’t know.

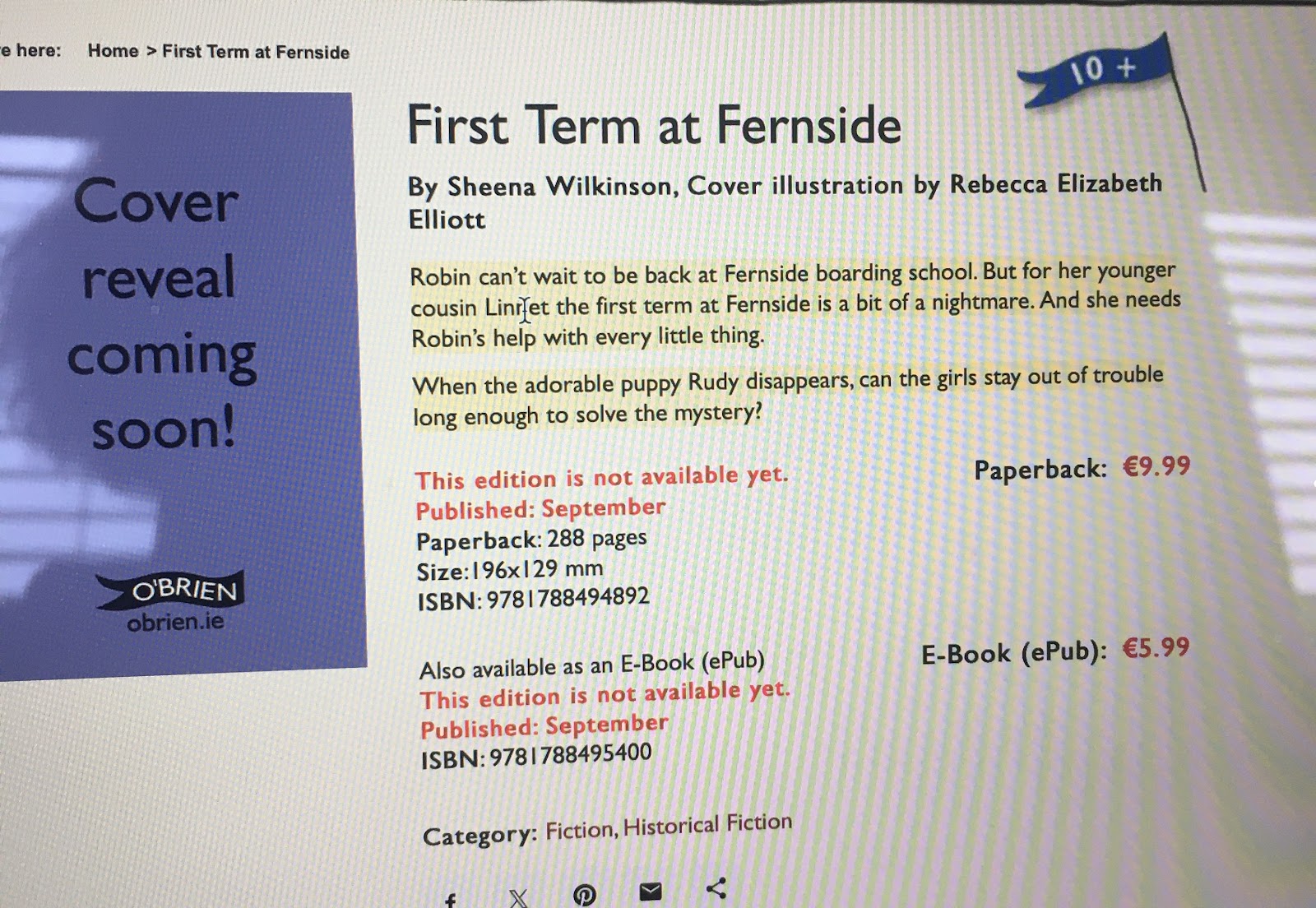

Thinking of length, I’ve noticed, on various books & education threads, that teachers often ask for class ‘read-aloud’ novels (often based on a school topic) but they mostly wanting titles that can be read within a half-term. Ah well. Maybe the WIP will need more editing than I imagined? So do watch your word count, especially if you want your book to be read for any of the children’s choice book awards.

Back to another super-reader factor: many seemed to download their titles. They were reading on screens, phones and kindles rather than through real-world books. Once a book was done, it was done and on one went to the next new title and the next new writer. This was not a market, perhaps, where a publisher’s spray-edged, special-gift-edition of a prized title would mean much. Reading, for this group, was the consumption of an experience, without any ownership of an object.

Besides,

within the current housing and rental market, is there any space for

filled bookshelves or a personal library, whether for the adults, or for

children? Surely, this absence must make teachers demonstrating the valuing

of books even more essential, culturally, along with the need for

good, well-managed public libraries?

I noted, also, that while many in the group got their books from charity shops, some stated that they never paid for books, even though they rarely mentioned library or use of an e-library.

They always got their books for free, they said, and only ever read free books. How? Were these titles promotional give-ways, delivered so the chosen reader would recommend that authors’ work? Or were they, I asked myself darkly, downloading free titles from the various pirate book sites? Harumph!

As I muttered on to myself, another point struck me. Perhaps these super-readers included ‘listening’ to books rather than reading from books with pages? The quantity suddenly suggested that this could be their form of reading.

Now the act of reading, to me (and especially reading with children) includes the visual pattern of print on the page, but many teachers and librarians also seem to say that listening is reading. The listeners hears the story, voice and vocabulary of the book just as validly as if they read the pages in a traditional way.

However, if these readers are ear-reading rather than eye-reading, what else they are doing at the same time, other than concentrating on their novel? Were they, despite having to accept the speed of the story, actually skim-listening or skim-reading? Who knows?

And there is that other small problem with the attention. I know that, although I have enjoyed many great ‘listens’ on audio-books, keeping your mind on the story is not always easy, especially when you are involved in another task or a busy activity. That's when I remember that turning back though pages feels a lot easier than rewinding and trying to find your place.

Besides, if you are in a comfy chair or bed, audio-voice makes it so easy to drop off to sleep . . . As you may be by now, after listening to all my questions, queries, suppositions and suggestions. Thank you for your patience.

But, honestly, reading twenty-five books in a month? That one historic tome may well be enough for me, and I am looking forward to it.

Have a great July - and please read as much or as little as you want.

Penny Dolan