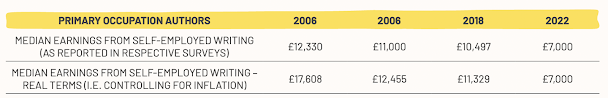

Lsat month I wrote about the impossible economics of writing books as a way to make a living. Several people asked how the economics works for publishers if it's so bad for writers. The truth is that it often doesn't, though it doesn't 'not work' to the extent described in the article No one buys books. I'm not going to dissect the article here as its limitations have been well analysed already. Instead, I'll let the much better informed GalleyBeggar answer the question What does a book cost? This is a great breakdown of how much it costs to produce and sell a book. Depressingly for those of us who scrape a living writing books, it just confirms that even with a publisher paying the unusually high royalty of 10%, an author who sells out the print run of 3,000 copies can still only expect to receive £2700 for the 300 page book that will have taken them at least a year to write.

One important thing to bear in mind is that authors can be paid in different ways:

Flat fee: all they get, ever, except perhaps money from collecting societies for library loans and photocopying

Royalty: a percentage of the money the publisher receives for each copy of the book, typically 5-10% but can be less or (rarely) more. Remember the publisher typically receives less than half the cover price

Advance: a sum paid in advance, against royalties. So royalties will only be paid once the book has 'earned out' — has gained enough 40ps or 50ps for sales to recoup the money the publisher has already paid the author. Most books don't earn out, so most authors never get more than the advance. (You don't have to pay the advance back if it doesn't earn out.)

There might also be some money from foreign rights deals.

(Some people will say 'yes, but then you get money from festival appearances/school visits/events'. Although some authors do, they are being paid for the day they spend doing that: it is payment for more work, it is not more payment for the book.)

Importantly, the publisher makes money even if the book doesn't earn out. Suppose a publisher paid an advance of £2000, with a cover price of £10 and the author earning 5% (and 5% to the illustrator), and the publisher got 50% of the cover price. The author would get 25p per copy. The book would have to sell 8,000 copies to earn out for the author, but that's more than are likely to be printed, so it won't. But if the publisher couldn't make money if the book sold out, they wouldn't publish it. If the publisher just covers costs and makes no profit, that only means shareholders don't get a dividend.* Covering costs means everyone has been paid for their work. As most people won't take a job that pays £2,700 a year, even for the supposed glamour of working in publishing, plenty of people are making a living — just not most of the people who write the books.

People who work in publishing are not well paid, but they are certainly paid more than most writers. The industry is sustainable only because there are more people wanting to write books than there are books needed, so plenty of people will subsidise their own jobs. This is why the battle to get wide diversity in book publishing will be lost. People who are poor can't afford to subsidise their job as a writer by working for way below the minimum wage.

*Incidentally, to earn £2,700 from just owning Hachette shares and doing nothing, you need to invest only £90,000 in Hachette. Rather than pay to do an MA in Creative Writing, invest the same money in Hachette shares as you would run up in student loan and you can earn as much as if you wrote a 300-page book every year for the rest of your life

Out now: 81 Mind-Blowing Biology Facts, Arcturus, April 2024