Have you got an advent calendar ready for next month? Feeling you need a daily treat to get you through? Or maybe, given all that's going on, you've opted not to bother this year and wait for 2021. Either way, I'd like to talk about my love of advent calendars, how I used one in my latest book and the parallel with slowly revealing a story.

|

| Getting ready to post some out |

A school librarian review awarded me the 2020 prize for Best Use Of an Advent Calendar in YA. Thank you, Flying Librarian, and thanks to my agent, my family etc, etc. Next best thing to the Booker Prize, obvs. While I chuckled, I was also really pleased that someone had spotted and appreciated the geeky time I spent playing around with the advent calendar and making it work in the book.

So why's there an advent calendar in The Rules? It grew out of a short story in I'll be Home for Christmas, which took place on 1st December in a bowling ally with Spotty Paul on shoe duty dressed as an elf and a sickly smell of stale mulled wine.

So when I came to write it into a full-length thriller, the run up to Christmas seemed a good idea for a tight timescale for the story. A ticking countdown is always helpful in a thriller to keep a sense of pace so; ta-dah - why not use an advent calendar to tick down the days? And, as I'm a pantser not a planner when I write a book, the advent calendar idea gave me a much needed day-by-day chapter structure to work with.

Girly swot that I am, I loved choosing the image to be revealed each day and working out how to subtly reference that in the chapter.

|

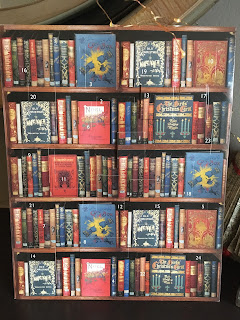

| My sister made an advent calendar to match the one in THE RULES |

Amber receives the advent calendar from her social worker, Julie, who's kind and well-meaning, in the face of being constantly pushed away and insulted by Amber. Julie sees that Amber is vulnerable and alienates anyone who tries to help her or get close so Julie, bless her, perseveres. Amber is not impressed with the gift asking Julie if she's eaten all the chocolates. But deep down (and with Amber you have to go very deep) the gift means something because when she has to bugout and go in a hurry when she thinks her dad might have found her, she packs the advent calendar in her Grab and Go bag.

Amber and Josh half-joke that it acts as a fortune teller and, although they don't really believe it, when Amber is at a very low point, she does look to it for help. Maybe there's a nod to the locked doors and windows she encounters in the past and the present. And I liked playing around with time and dates - we're never truly sure of Amber's past timeline and how much time elapsed in her different experiences. By the end of the novel, we see that she always needs to know the time and date and the calendar represents that for her. Finally (*mild spoiler alert*) we know that the biggest door - number 24 is still to be opened. What will it reveal of Amber's future?

So, the advent calendar turned out to be useful in ways I hadn't anticipated. I liked the parallel with the novel and its structure being a gradual reveal of what happened in the past to Amber, and seeing where each of these calendar days is leading her now. We get a little piece each day. And that was very satisfying to write - and hopefully to read.

The calendar in the book, brought to life by my sister during Lockdown, is based on the ones I used to get as a little girl, showing a typical Christmas or snowy scene and shedding non-eco glitter throughout December. I've continued the tradition of advent calendars with my own kids and my goddaughter. And I sent one to my lovely editor when she was doing edits on the book last December.

We've had the full range of novelty ones across the years - LEGO, Playmobil, stationery and toiletries. And I've done the lovingly curated homemade version too - once! That was a lot of work.

And, of course, there's always chocolate. My youngest has been known to scoff the lot in the first few days which was completely horrifying for me and my lifetime of delayed gratification. You absolutely cannot open a window early! No! And eat the chocolate!!! No, no no! It's partly superstition on my part growing up with the ultimate superstitious mother who was always saying 'Hello' to magpies and chucking salt over her shoulder. I put a tad of that superstition into the book.

So what's my advent calendar this year? If money was no object, I'd be going for the full-on feasting Fortnum and Mason version:

And I'd be up for The White Company mega beauty one:

Maybe there's a book one...And if there isn't, please make it, somebody.

But alas, all my fantasy advent calendars are rather pricey. And the Scrooge and sentimentalist in me has pulled out of the cupboard a simple cardboard bookish one I bought from the Bodleian Library shop in 2018 - when the world was rather different. I've squashed down all the windows and it'll do for 2020.

Tracy Darnton is the author of The Rules, winner of the prestigious "Best Use of an Advent Calendar in YA 2020" award (Yes, it's a thing). You can follow Tracy on Twitter @Tracy Darnton.

*This blog updates one used in my blog tour for THE RULES and kindly hosted by Sarah and Sophie @TLCCBlog which you can read here