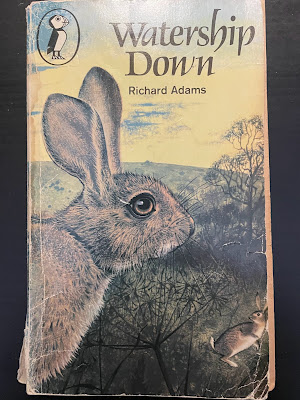

The book which won the Carnegie Medal in 1972 is one which should give hope to all budding authors, especially to those who have been rejected by publishers, and even more especially to those who have been rejected multiple times by both publishers—some say 7, some say 30—and agents, because that's what happened to Watership Down by Richard Adams. It was ridiculously long; it had obscure quotes from Tennyson and Malory for chapter headings and it was about a bunch of talking rabbits. Of course they rejected it.

And then Rex Collings decided to publish the book, risking his own money in the venture, and the venture was wildly successful. Watership Down won both the Carnegie Medal and the Guardian Prize. It was subsequently taken on by Macmillan in the USA, translated into 18 languages, filmed and made into TV series more than once. The movie even spawned a No1 hit single in Art Garfunkel's Bright Eyes although Richard Adams hated the song. In other words, Watership Down was a phenomenon. It was also, like that other much-rejected book, Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone, published in a parallel edition with an 'adult' cover. Interesting, then, to read what Richard Adams said about rules:

'I believe that writing is rather like chess, in that although there are certain useful rules to bear in mind, a lot of these really should be torn up at discretion. One can easily get so blinkered by the rules that one can no longer judge a book by the light of the heart. That light, of course, is what is used by children themselves . . .' (In Chosen for Children, The Library Association, 1977)

I re-read Watership Down recently and when I'd finished it seemed to me that the key to its success was in the brilliant realisation of landscape and weather. So much in the book is wildly fantastic—rabbits with a complete and complex language and mythology, rabbits with telepathic, seer-like powers—but because the action is precisely located (all the locations are real places), and because we see the landscape from a rabbit's point of view, it's somehow easier to accept that Fiver can forsee disaster and that rabbits gather round in the evenings to listen to stories. In addition, Adams created a handful of memorable characters. There is Hazel, the reluctant leader who is drawn with great subtlety and skill, and there is the battle-scarred warrior, Bigwig, who Adams based on the self-sacrificing character of Elzevir Block, the hero of Moonfleet. There is General Woundwort, the terrifying leader of the Efrafa warren, and inventor of its totalitarian regime, and finally, there is Fiver himself; the fey, unpredictable and vulnerable rabbit without whose insights (and foresights) all the rabbits would have been doomed.

Adams was open about his literary influences, and first among these was Walter de la Mare. Adams was 52 years old when Watership Down was published. He was born in 1920, and de la Mare was at his peak of popularity during the 1920s and 1930s and was thus a strong presence in Adams's childhood. Adams says of de la Mare's poems that they 'are informed throughout in the most disturbing manner by a deep sense of mankind's ultimate ignorance and insecurity. The poems are comforting because the words, sounds and rhythms are so beautiful; they possess and confer dignity; and they tell the truth.'

I'm not sure that Adams manages to be as disturbing or as strange as Walter de la Mare, because when you set aside the rabbityness, Watership Down is really a fairly straightforward picaresque adventure story with more overtones of John Buchan than of de la Mare, despite Adams confessing that the character of Fiver owes much to the character of Nod in The Three Mulla-Mulgars. The Three Mulla-Mulgars, by the way, or The Three Royal Monkeys as it's also known, is probably one of the most influential children's books of the twentieth century, influential on children's authors I should say, and despite its sometimes difficult language is well worth a read today.

Add all this together and you have what is really a quite old-fashioned kind of book; yet another Carnegie winner which is shaped by the shadow of war. And it has its flaws. Ex-soldier Richard Adams conceived his group of rabbit survivors as a kind of military platoon, complete with mild-mannered but brave and intelligent officer type (Hazel), and gruff and grizzled NCO (Bigwig). I'm speculating here, but I can see how the plot might have developed from this. We have a group of chaps escaping disaster. Great. Jolly brave chaps too, but then, oh dear, we need the girls to dig warrens and produce babies. Disaster! What can we do? Better find some does. There you have the whole structure of the book and I suspect that having come up with such a neat plot it never crossed the author's mind to alter these fundamentals.

But imagine for a moment that this wasn't the case; that male and female rabbits had escaped together and that Adams, who relied heavily on R M Lockley's book The Private Life of the Rabbit, had not chosen to ignore Lockley's description of the matriarchal society of rabbits. Those rabbits could still have raided the farm for food. Hazel could still have been caught and freed again, and the conflict with the neighbouring warren at Efrafa could have come about in any number of ways. They might, for example, have been appalled at the way all the rabbits in Efrafa were treated, and wanted to set them all free, rather than just stealing the does. Then we wouldn't have been confronted with these rather foolish male rabbits who don't even know how to dig a hole, and female rabbits who the males only want for breeding and hole-digging.

I've seen this kind of thing before in a Carnegie winner—you may remember Ronald Welch's Knight Crusader, which almost succeeded in ignoring women altogether. Welch was another military man, and I can't help thinking of my war-hero uncle, a lovely man who treated young women with tremendous courtesy and charm but clearly saw them primarily as home-makers, though he didn't expect them to dig holes.

I started thinking about how many of the Carnegie winners had been influenced by the reality or the memory of WW2 and I happened to glance ahead to some of the other 1970s winners. There's The Machine Gunners, The Exeter Blitz and Thunder and Lightnings coming up soon, and on the playground in The Turbulent Term of Tyke Tyler the kids are still chanting rhymes about Hitler. It makes me think about time and history. From 1975 back to 1945 is only 30 years. Nowadays 30 years doesn't seem that long to me, and most, if not all, of the children's authors writing in the 1970s were old enough to be affected directly by the war and its aftermath. So it's not surprising that it finds its way so frequently into their books. But I wonder what a child makes of this, because to them thirty years is an eternity. It shocks me now to realise that, when I was born, the start of WW1 was only 40 years in the past and that's how long ago (more or less) my own daughter was born.

By a strange coincidence another book about animals in trouble was published in 1971, just a year before Watership Down and on the other side of the Atlantic. This was Mrs Frisby and the Rats of NIMH by Robert C. O'Brien, which won the Newbery Medal in 1972, the same year as Watership Down won the Carnegie. This book, too, deals with a group of animals whose lives and homes are threatened by human activity, but in this case the fact that the animals can think and talk is a result of human experiments on a group of rats and mice which has resulted in the rodents becoming intelligent enough to read and, more importantly, to escape. In another example of synchronicity the animals in both books are helped by a bird—a seagull named Kehaar in Watership Down and Jeremy, the crow, in Mrs Frisby. I have to say that I find Mrs Frisby a lot more fun than Watership Down.

Talking animals were not new in 1972, and it's probably not an accident that the rabbits in Watership Down tell stories about a 'trickster' rabbit called El-ahrairah, who harks back to Brer Rabbit himself, and maybe even to the Winnebago Hare myth. For me though the problem is that Richard Adams' rabbits are not really rabbits at all. They're a group of soldiers lost in enemy territory, or a group of refugees seeking a new home. They may have a rabbit 'language' and 'mythology', they may dig warrens and go out to 'silflay', but it's as humans that we recognise their characters and their interactions, in the same way that in Animal Farm the 'animals' are humans in disguise. It's a funny thing, but even though they wear clothes I feel that Beatrix Potter's rabbits are more convincing, as rabbits, than those in Watership Down, but what do I know? I'm firmly on Mr MacGregor's side of the fence after 40 years spent trying to keep them out of my vegetables.

|

| From The Tale of Benjamin Bunny by Beatrix Potter |

And all those foolish publishers and agents back in the early 1970s?

What did they know?