Previous posts on this blog -- particularly Paul May's wonderful series about past Carnegie Medal winners, have reminded me of many old favourites, which is possibly why recently, at the Bristol Conference (essential for anyone who’s interested in vintage children’s books), I did a talk on the English writer Mary K. Harris (1905-1966). I’ve noticed that people either say, Never heard of her, or Oh gosh, I love her! I’ve so far met nobody who’s read Harris’s books without them having left a positive impression.

Mary K Harris is, I would argue, one of the most undervalued children’s writers of the mid-20th century. She was not without recognition in her day, nominated twice for the Carnegie Medal. She published 16 books for both adults and children, between 1941 and 1968, of which several, as far as I could discover, seem only to have been published in America. Certainly I couldn’t find any copies. Her British-published books are long out of print, but can be found online.

However, not much else can, which makes me doubly grateful to the Encyclopaedia of Girls’ School Stories, edited by Sue Sims and Hilary Clare, for supplying more information. Born in Harrow, Middlesex, in 1905, Harris was educated at Harrow County School for Girls though she is not listed in the school’s list of distinguished alumnae. Her parents separated, and she lived with her semi-invalid and demanding mother. They weren’t well off, Mary did all the housework, and even after her mother’s death, she looked after an elderly aunt until she herself died, of throat cancer, at the young age of 60.

It doesn’t sound very cheery, does it? And though her books are delightful, they definitely reflect a life of compromise and maybe sadness – their world view is not an especially jolly one.

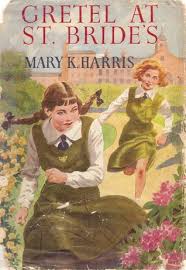

Harris’s novels are a mixture of home and school stories. Gretel at St Bride’s (1941) and Henrietta at St Hilary’s (1953) are set in traditional girls’ boarding schools, with the first being most notable for its heroine being an Austrian refugee.

In Emily and the Headmistress (1958) Emily is left at her boarding school over the holidays. Harris likes writing about empty schools, evoking vividly the atmosphere of a building left without people. Given how mean some of her own characters are, and her comments about the horrible children she was at school with herself, perhaps she preferred them that way! Emily is interesting as it foreshadows her interest in older characters as more than just necessary background – like Noel Streatfeild, she’s very good at adults generally.

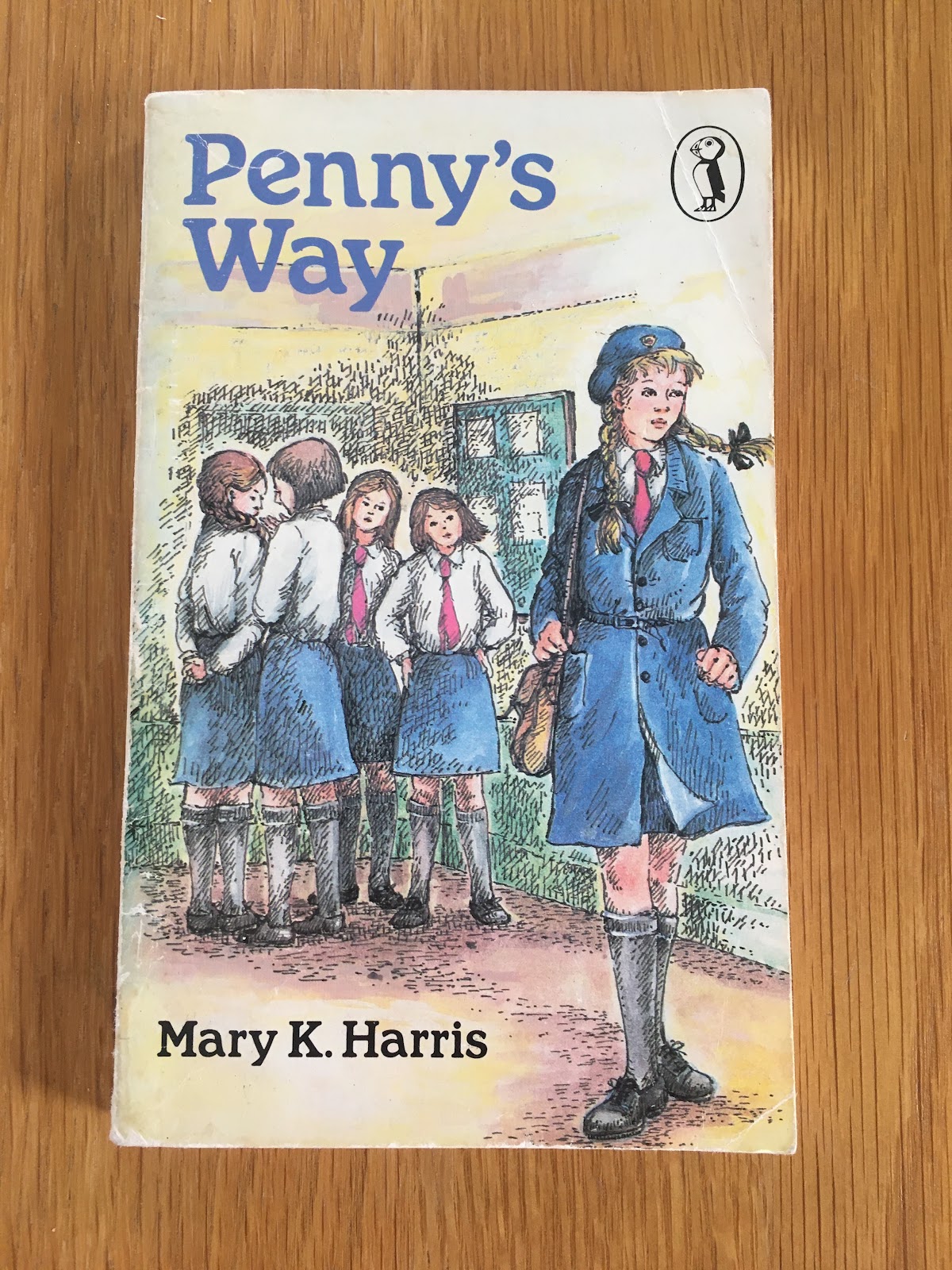

Seraphina (1960), Penny’s Way (1963) and The Bus Girls (1965) are set in girls’ grammars, with none of the heroines quite fitting in – Seraphina, an orphan, is more or less dumped in the school’s boarding house.Penny, living above a fish and chop shop, struggles in the bottom form of her grammar school, while Bus Girl Hetty is delicate, and has a single, seamstress mother, struggling to make ends meet and almost afraid of the clever daughter who has grown far beyond her.

In Jessica on her Own, Jessica, the middle and difficult daughter, goes to the secondary modern where, though it’s never stated – a great deal is unsaid in Harris’s books – it’s clear she is posher than the average pupil. This is Harris’s most modern book. There is talk of drunken orgies and Freedom from Hunger marches. A far cry from the Chalet School or Malory Towers.

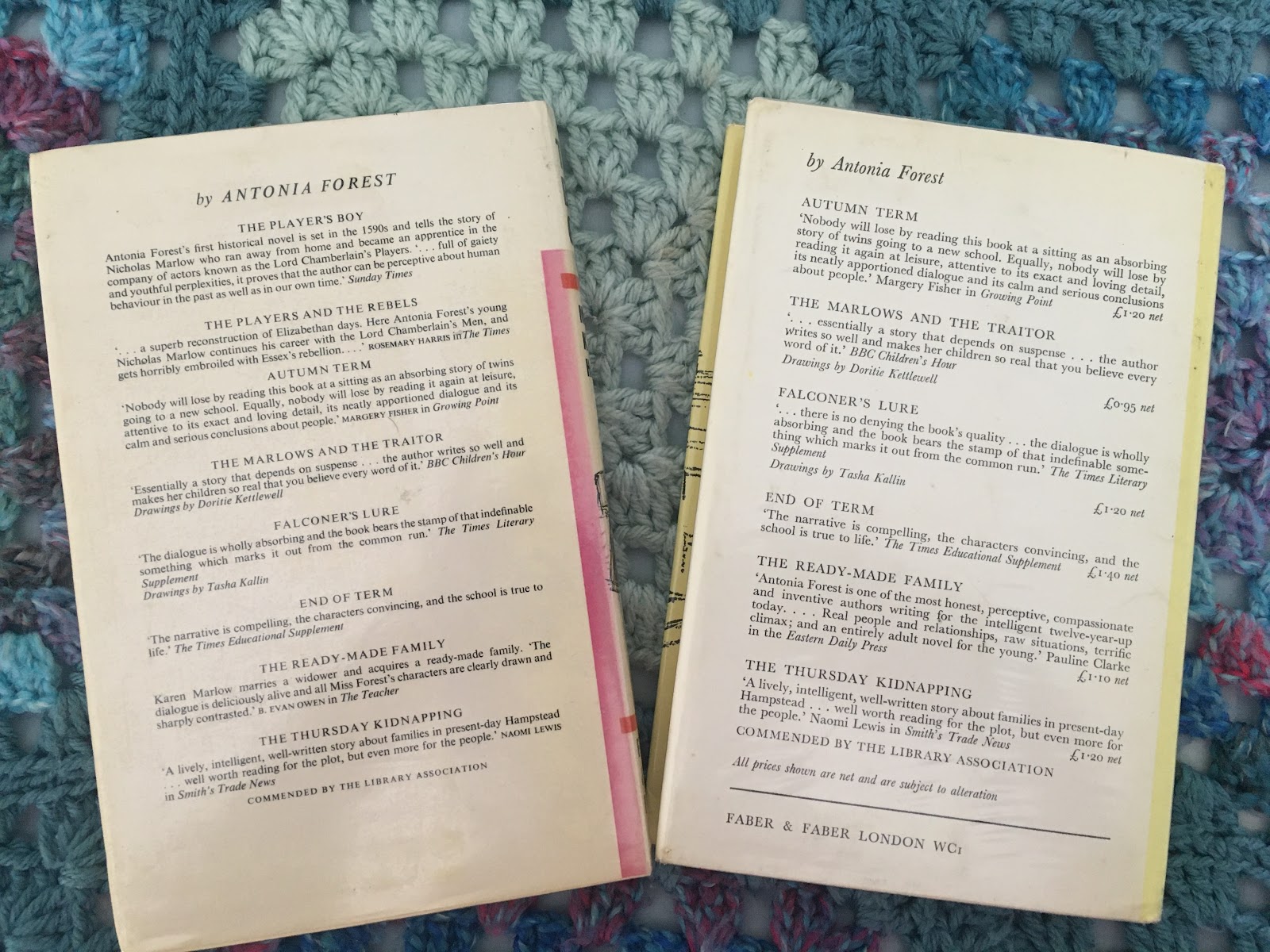

When I chose to talk about Harris, my own memories of reading her were rather vague. I remembered well-written, thoughtful books, where the main action was interior rather than exterior. I always linked her in my mind with Antonia Forest, with whom she shared a publisher, Faber, and whose books were actually advertised on the back of several of Harris’s novels.

And certainly I, a Forest lover, was influenced by that subliminal ‘if you like this, you’ll like that’ messaging.

The two writers are very different – Forest’s milieu is much posher, but they share a deep exploration of character and a refusal to romanticise either school life or human nature.

There’s also a kind of sadness in her books which reminds me of Nicola Marlow’s inarticulate grasp of the complexities of the human condition when she learns the Latin phrase sunt lacrimae rerum. In Mary K. Harris’s books, there are always tears of things. But strictly of the unshed variety – a kind of quiet desperation rather than an old-fashioned stiff-upper-lip. Her heroines suffer. Not exactly the torments of the damned, and they don’t have to save the world or anything tiresome and high concept like that, but they all suffer loneliness, inadequacy, unpopularity – learning early the lesson that life can be difficult.

Which I hope is in no way to suggest her books are miserable – far from it! She’s a prose stylist of wit and charm. She can be very funny – in the sharpness of her observations, the pithiness of her dialogue, or in some of the pickles her luckless heroines stumble into. For example, when the ever-helpful Penny agrees to go to the dentist in place of her ghastly friend Mavis, believing he will find one mouthful of teeth to be much the same as another, and then finds herself with a new filling and a bill for a pound – a lot of money in 1963, when you’re only 13 and you live in the flat above the chip shop.

Her settings are both vividly evoked and varied, both geographically and socially: though we have no great extremes: nobody is either very rich or very poor. Seraphina is set in a small midlands town, The Bus Girls in a windswept East Anglia. In Penny’s Way the family move, for financial reasons which are never really spelt out – possibly because neither Penny nor the child reader would understand – to a flat in a busy high street, whose sights, smells and sounds are vividly rendered as Penny hurries through the lighted dusky streets. Jessica’s home is professional middle-class suburban.

Harris has a particular ability to evoke atmosphere, should that be around the family tea table, in the dormitory of a girls’ boarding house, the bustling lamplit high street where Penny’s family live; the baking hot suburban summer of Jessica on her Own; the Suffolk marshes in The Bus Girls: It was a little seaside town of clean colours and salty smells.

I find some of her heroines slightly reminiscent of some of Streatfeild’s more awkward characters – especially Jessica, the prickly middle child and Penny the hapless youngest in a clever family. Hetty is rather sharp and dismissive of the nervous mother who’s seeing her daughter grow far beyond her – which must have been the case for many grammar school children at that time. As so often happened, Mrs Grey never knew how to reply to Hetty’s remarks.

Harris renders with at times painful realism the lonely helplessness of being a young teenager. All three girls have families – in Hetty’s case only a mother, who love and appreciate them, though Hetty’s mother is clearly rather frightened of her. Yet they struggle with self-esteem or to find their place in their society. Their eventual triumphs are quiet ones too – the realisation that one is not quite as dim and unlikeable as one believed is about the most a Harris character can hope for.

Seraphina, the only one to tell her story in the first person has more to grumble about than most Harris heroines, though she is blessed with a high intellect, a methodical mind and – something I was always envious of as a child – long red plaits. She’s also the only one with a romantic, children’s-bookish background – abandoned as a baby, she’s been brought up by a kind granny, whose death takes place just before the start of the book. She’s taken in by nice neighbours, but their house is as full of people and mess as it of love and welcome, and off she has to go to hairdresser Aunt Edna, who clearly doesn’t want her. So far, so standard classical kidlit, but Seraphina doesn't get a happy ending. She doesn’t discover a secret talent and the wonderful friend Stephanie is taken away from her by her fairytale ending. Rereading the book as an adult, I was struck by its sadness in a way I wasn’t as a child. It’s one of the loneliestbooks I’ve ever read. Seraphina tells us that her habitual neatness and competence – which don’t endear her to her new schoolmates – are in case her parents should return and claim her – she wants to be found worthy. But – sorry for the spoiler – they never do come back.

And Aunt Edna, disgusted by Seraphina’s efforts to weave a fantasy life for her mother, tells her a few home truths:

The facts are these: your mother dumped you on Gran from the day you were born, and she’s never lifted a finger for you since… Rosalie … was as hard and selfish as they make them… I’m sorry to be so blunt, but you’re fourteen now and should know the truth…

If it’s not much fun being a child in a MKH book, there’s little to look forward to when you grow up. Aunt Edna is a monster, but she probably didn’t want to take charge of her pretty sister’s sulky, bereaved teenager. Hetty’s harassed widowed mother is terrified of the telephone and often of her clever, sharp daughter; Penny’s mother is trying to adjust to living in the flat over the Fish and Chips, dealing with a demanding family; Jessica’s mother Lydia is a Cambridge graduate and former geography teacher who is clearly finding life as a wife and mother rather less exciting than she’d like – until her twin sister is killed in a car crash which probably is quite exciting though not what she’d have hoped for, leaving a traumatised orphan, Isabel, for her to bring into her own family – which she does with a great deal more alacrity than Aunt Edna, but with rather unfortunate consequences.

There are no obliging maids or nannies to help with anything; and the men aren’t up to much either. Edna is single; Hetty’s mother is widowed; Penny’s father is mostly silent, disappearing from meals when his children’s squabbling makes his ulcer play up. Jessica’s father, rather dashingly for 1968 a physiotherapist, is about the best of them but even he doesn’t do very much.

As you’d expect, the teachers are nuanced and human too. There are kind headmistresses and fierce, sarcastic form mistresses, often bringing a sense that they might actually, for all their idiosyncrasies, be human beings. The aptly named Miss Wolff in Penny’s Way surely owes something to Antonia Forest’s Miss Cromwell. ‘There is no need to consult your watch, Sylvia. I am quite capable of being your time-keeper.’

I’m particularly fond of Jessica’s form-master Mr Berryman: He was a heavily-built man, with small beady eyes. He did not look particularly nice, but he was nice. Unfailingly kind and always cheerful, he would throw himself down on one of the ordinary school chairs without ever a thought that it might crack beneath his fourteen stone.

As for friendship among the girls, that too is complicated. Friendships ebb and flow much as they do in real life. Seraphina makes an engaging, if chaotic friend in Stephanie, but Stephanie’s own good fortune takes her away. Well-meaning Jenny is desperate to be Seraphina’s friend, but Seraphina treats her badly, though her guilt about that, and her efforts to make up for it, are a crucial part of her self-development.

Penny’s former friend dumped her when she was moved down to the bottom stream. Her so-called friend Mavis is jealous of Penny and always eager to take her down (‘Do I smell a fried-fishy smell somewhere?’) But the narrative voice invites sympathy for Mavis: Poor Mavis; if she went only where she was welcome, she might never go anywhere. And Penny grows close to the much nicer Nicola instead.

Jessica’s friend Nance is sharp and chippy, though loyal and brave – and they spend as much of the book fallen out as they do together. There are also boys to complicate the dynamics of Jessica’s class.

Davina in The Bus Girls blows hot and cold, and behaves badly not only to Hetty but to the rest of her form. When she shows Hetty at the end of the book that she does want to be her friend, I for one wondered how long it would last.

Some of the virtues for which girls would be rewarded in more conventional stories aren’t always appreciated. I don’t like Ann particularly but she is quite the nicest person I know.

So, how would I sum up Mary K. Harris’s books? Quiet. Thoughtful. Realistic.

Life is tough. People are hard to read or inconsistent. Friendship is complicated. Schools – and she wrote about all sorts of schools – are difficult communities to negotiate. And being a grown-up will bring its own compromises and challenges.

There are days, Penny reflects, when home can seem quite depressingly ordinary

In their very ordinariness and their pain, Harris’s novels seem to form a bridge between the traditional school story and the grittier teen novels which would follow in their wake.

And they express that ordinariness with wit, charm and a deep understanding of what it is to be human, and especially what it is to be female. I hope you’ll discover – or rediscover them – for yourselves.