This story starts just before the Chernobyl disaster, and deals with its aftermath, both for the humans who were forced to leave their homes, and for the animals which were abandoned to their fate.

It begins with a wolf, which has been driven out of its pack and is starving. He comes across a house in the woods, where there is also a chicken house. But just as he is about to launch an attack, an old woman comes out. She doesn't have a gun, she doesn't shout. All she does is walk towards him, staring silently, holding a broomstick in front of her. The machinery and the huge buildings he had seen were beyond his understanding. This creature was not like that. She was of the forest, like him. But she had a power of her own, and it made his hackles rise. He turns, and runs away.

So we know that animals will be part of this story, as will a hint of wild magic. The magic is only a hint: it's not a large part of the story. But it's a thread that keeps emerging. The world of the animals, on the other hand, is the most important part of the story. They are not anthropomorphised: these animals don't talk. McGowan imagines how life looks and feels to them, and it's not always pretty. It's a very long time since I read Jack London, but Dogs of the Deadlands reminds me of his great classics, White Fang and The Call of the Wild - I suppose on an obvious level because they too deal with wolves - and it reminds me very much of Barry Hines's more recent classic, Kes: it has the same acceptance that life is tough, and that the wildness of nature should be accepted, and not sentimentalised.

The human story concerns a seven year-old girl called Natasha. At the beginning of the story she is living in Pripyat, the city close to Chernobyl. She believes herself to be the happiest child ever, because she has been given a puppy for her birthday: it's pure white, with one blue eye and one brown one - a detail which will be important in the story. And, her father believes, there is a little bit of wolf somewhere in her ancestry.

But Natasha's happiness is short-lived - because that very night, the accident in the reactor at Chernobyl happens, and all the people in the immediate area are evacuated. But they are not allowed to take their pets: Natasha is forced to leave her beloved puppy behind. This event overshadows her entire life.

For most of the story, we are with the dogs of the Deadlands. But we check into what's happening with Natasha, and eventually the two strands are woven together again. But in the meantime, we run with the dogs - and the wolves - and we see how incredibly hard life is for them: survival is very far from being a given. There are fights to the death, starvation always threatens, periods of contentment never last long. If you watch Autumnwatch, you'll know what I mean when I say it's much more Chris Packham than Michaela Strachan: there is no sentimentality. (The difference is that if a hedgehog predates the young of a ground-nesting bird, Michaela will be upset: Chris will point out that the hedgehog needs to eat, and it was actually rather clever of it to find the nest.)

|

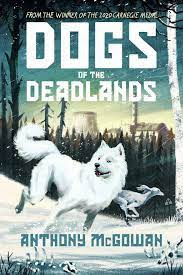

| The book is illustrated by Keith Robinson. |

It's a powerful story, with moments of tenderness and a profound understanding of nature and survival. And if it all sounds a bit bleak - well, just wait till you get to the end. The last section is a bravura piece of writing that will have you weeping, smiling and cheering all at the same time.

The book is marketed as being for readers of 10 and above. I hope it will also be found by the many adult readers who would enjoy its deep connection with the natural world. It's a great story.

1 comment:

Crikey, Sue - to be read when one is feeling pretty resilient!

Post a Comment