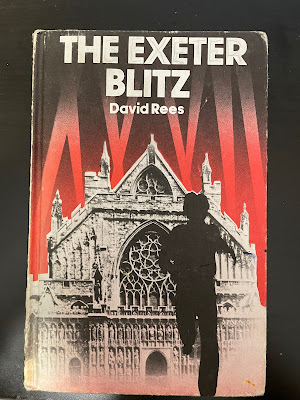

Several times now I've read that the real central character in the 1978 Carnegie winner, The Exeter Blitz by David Rees, is the city of Exeter. The novel describes the experiences of the fictional Lockwood family on the night of the 3rd-4th of May 1942 when a massive German bombing raid destroyed much of the city. This bombing raid was part of a German retaliation for the Allied fire-bombing of Lubeck earlier that year. The Baedeker Raids, as they were called, targeted English cities of particular cultural importance and took place mainly in April and May 1942. David Rees's book reminded me of a TV drama-documentary where, to give a bit more focus to the recycled archive footage and add human interest some invented scenes are recreated by actors in the studio. The book also slightly alters history. David Rees says in his introduction: 'The story is not intended to be an exact reconstruction of the events in Exeter of the night of May 3rd-4th . . . The magnitude of the disaster, is, however, meant to be historically accurate.'

I had problems with this book, a book which has its strong advocates, especially in Exeter, where David Rees lived and worked for most of his life. I think the reason that people say that Exeter itself is the central character is that the documentary parts of the book feel real, while the fictional characters are unconvincing. The central (human) character is Colin Lockwood. He's trouble at school and trouble at home and he stands improbably on the cathedral tower watching the bombers come in and the bombs fall. Colin, like the city and the rest of his family, survives the night but is much changed. During the course of the night he discovers that the teacher he hates is an ordinary, decent person and the evacuee boy who is his mortal enemy is also an ordinary, decent person. The teacher is killed, along with his wife, but the evacuee survives and the boys become friends. These might be thought to be spoilers, but you can guess what's going to happen from the beginning. This is not a story which is full of surprises, though there are one or two.

Taken on its own the coming-of-age story about Colin didn't really engage me, though I did have some sympathy for his long-suffering family, But the description of the bombing raid and its aftermath is powerful and gripping. The device of using this fictional family and placing the various family members in different locations in the city works well, in the same way that a movie like Saving Private Ryan, for example, makes sense of large events by focussing on a few individuals. But I couldn't help comparing this book to that earlier Carnegie winner, The Machine Gunners and it seems to me that while Robert Westall took real-life experience and used it as the inspiration for a work of fiction, David Rees created what feels like a piece of journalism disguised as fiction. I could be wrong, but I don't think David Rees was actually in Exeter when the bombs fell, and even if he was, much of this account would have had to be stitched together from accounts in newspapers and elsewhere. That's not necessarily a bad thing but, for me, when the research starts to show through, a novel becomes less effective. And novels are about people, not about cities. Even Ulysses, that most famous example of a book where a city is sometimes held to be a character, is essentially about Dublin's people, and the city's people and places are realised through one of fiction's most minutely described and inhabited characters.

The final lines of The Exeter Blitz are the most ill-judged of any of the Carnegie winners I've read so far. Any sensible editor would have just said 'NO!'

|

| My grandmother in the back garden of the house that was bombed in the early 1950s |

As it happens, my mother, now 95 years old, experienced one of the Baedeker raids first-hand. She had just turned 15 and was living in a council house on Colman Road in Norwich (now part of the city's ring-road) when her dad burst into the house and yelled at the family to get into the Anderson shelter because the Germans were 'machine-gunning all along Colman Road'. Some people's shelters, my mum told me yesterday, were 'like little palaces inside', but theirs was just bare earth and possibly something to sit on. While they were in the shelter an incendiary bomb came through the roof of the house, went through the bed in my grandparents' bedroom and through the floor to the room below. The bomb didn't explode properly but the ARP wardens threw the feather mattress out onto the tiny lawn in the back garden where it exploded in a cloud of feathers which my mum says she can still picture as if it was yesterday. Although yesterday is not something my mum remembers too well these days - or indeed what happened ten minutes ago. But on the events of eighty years ago she's still pretty good!

The family were able to stay in the house despite the holes in roof, ceiling and floor but many Norwich residents, like those in Exeter and York and Coventry, were not so lucky. The Baedeker raids received this nickname because it was said that the German commanders used the famous guides to select targets with cultural significance - and they had useful maps too! The two raids on Norwich in April and May 1942 killed 229 people and a further 1000 were injured. And apart from the major damage inflicted on the city centre more than 2000 domestic properties were destroyed and an incredible 27,000 suffered some damage - that's out of a total of 35,000. It's hard to believe that my mother lived through being machine-gunned and bombed in a quiet provincial city.

In fact, my mother's recollections of the war are more about excitement than fear. War ultimately represented an opportunity for her to escape from Norwich by joining up as soon as she was old enough. She was able to travel, meet my father, and learn to drive. The army gave her freedom.

The Exeter Blitz feels like a very old-fashioned kind of a book, and if someone had told me it had been written in the 1950s I'd have happily believed them. There is something slightly teachery about it and I hadn't really noticed that kind of thing in a Carnegie winner since reading Edward Osmond's A Valley Grows Up back in 1953. If you want information about the Exeter blitz it's a good resource. If you want novels that say something powerful about the experience of living through WW2 then I'd go for Susan Cooper's Dawn of Fear, or The Machine Gunners.

It is astonishing to me that Susan Cooper has never won the Carnegie, and good to know that her adopted home, the USA, rewarded her with the Newbery Medal in 1976 for The Grey King.

No comments:

Post a Comment