|

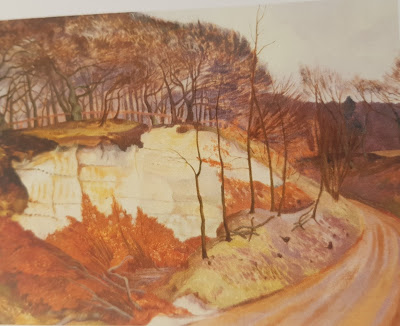

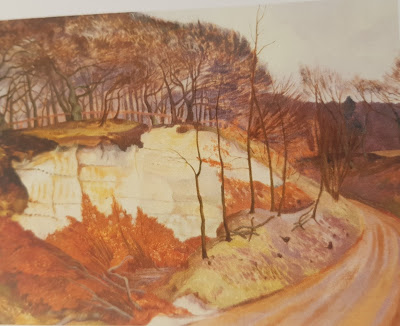

Whiteleaf' by John Nash

|

The Ghost Beck

Where she rises when she chooses

to break cover is some way below

Chalk Hill Wood though not

down as far

as Barrow Pit Meadow but

exactly where

her source is the dowser

cannot tell

saying she surfaces each

seventh year

is not more than an old wives'

tale

come each spring the pond

beside

the surgery turbaned with

old bulrushes

starts swelling filling and deciding

as often as not to overflow

and making haste for the Hoste

coursing through the Green

flashing or glimmering surprising

drivers on their last leg to the coast

and splashing the windscreens

of those who disrespect her

until tiring no longer diaphanous

faltering fading she becomes

little more than a dark stain

and then

one late afternoon just

disappearing

a ghost lost to herself again.

Welcome, Kevin and thanks for agreeing to talk to us for the second time.

It's a pleasure! As people around here say, without particularly expecting an answer, 'You all right, then?'

Just fine and dandy, thanks, Kevin - and good to know that you are too.Now, whereas last time we were focusing on the different aspects of King Arthur, this is the latest in a series of interviews about landscape and how it affects a writer both in their writing and in their life. Now, when I think of you, I immediately think of the Norfolk landscape evoked in collections like ‘Waterslain’ and ‘The Breaking Hour’, but the landscape of your childhood was a very long way away from that, wasn’t it?

True! Or partly true! The primary landscape of my childhood was the Chiltern Hills and their beechwoods; a scape so kind, so accommodating, so full of humps and hollows and secrets. That's where I was born, and where I lived until my parents moved to West Hampstead in London when I was sixteen. Well, actually that's not quite right. Because of my father's work, we lived in Wilmslow and Whaley Bridge during the last two or three years of the war. Our cottage in the Chilterns was at the top of a village called Whiteleaf - right at the foot of Whiteleaf Hill and its chalk cross, more than 150 foot high. I spent hours and hours scrambling up and down the cross from the chalk pit at the bottom (superbly painted by John Nash) to the prehistoric barrow at the top. And from my bedroom window, I could see right out across the Vale of Aylesbury.

Those people who have read your beautifully observed and remembered childhood memoir, ‘The Hidden Roads’, will be aware of your childhood museum, which you returned to in your recent collection of poems and photos, ‘Seahenge.’ Can you imagine we’ve paid admission and take us on a guided tour?

What a lovely invitation! The moment I saw it, my heart sang. Here we go then. The museum-shed has one window and looks onto our cottage just below it. Behind it is our garage, housing our battered Morris 10, and rows of gooseberry bushes.

Immediately inside the wooden door, on the right, is the visitors book standing on a medieval oak lectern, lent to me by my father.

Please sign it. You'll be in good company. All my childhood friends, and several of my parents' friends who live round and about, including Rumer Godden and Jacob and Rita Bronowski.

|

Objects from the Museum

|

Now then! Under the window there's a rough table and display of coins. The showpiece is a collection of Victorian bun pennies and halfpennies. From time to time I clean these, well knowing they'll be tarnished by the next day, but still delighting in their brief sheen and gleam. They share this table with several Egyptian antiquities, lent by my father on condition I write little descriptive labels for each of them, but I give pride of place to the most beautiful Roman perfume bottle dug out of the sand near Alexandria, and presented to me by a retired Classical archaeologist - I wish I could remember her name - who has just come to live in the village. Blue glass, a silvery bud no bigger than a crab apple, a long, slender neck. It's very beautiful, and I've dropped it twice during the last 70 years without damaging it.

At this rate we'll be in the museum all morning!

On the far wall, my father and I have built shelves out of bricks and planks. Three levels. On the top level, leaning against the wall, there's my drawing and a card: 'Whiteleaf Cross, once a Fallic symbol.' I never asked, and I don't think my father ever thought it necessary to explain. Christians have always been very good at converting what they can't suppress.

On the lower shelves at the far end are the choice pieces of Iron Age pottery that my father and I have found locally on Kop Hill and Bledlow Ridge and elsewhere. Lips, parts of handles, bits of base. Once, I reckoned that over the years, we'd picked up some 30,000 pieces and - you've guessed it - I spent hours and hours unsuccessfully trying to fit them together.

|

Roman Constantine Coin found on Kop Hill and meticulously recorded. |

Let me just point to a couple more items, and then we'll get some fresh air. Here's the Roman coin I found on Kop Hill. The size of a cartridge its metal cap. On one side is the head of the Emperor Constantine, the man who in 312AD accepted Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire. Here's his name. And on the other side, here are two centurions, their spears planted in the ground, and lettering I can't make out. It's warm now in the palm of my hand, a palpable link between then and now; Rome and an English outpost; and the person who dropped it and looked for it and couldn't find it - and me.

And the last item. . . not the fossils, not the ores, not the medieval key or the little leather gunpowder charger. Not the medieval tiles, now in my possession. No! Just a space, a small space, always waiting. . .

Thanks so much for the tour, Kevin, and for making so clear the origins of that early fascination for objects picked up and gifted.

|

| Roman Perfume Bottle |

That place was the corner-stone of my interest in the past. A place where my father encouraged me to be curious, to find out, to record. A place where my imagination raced. What I think I think (!) is that my writing quite often begins with the sensory (so, for instance the sight and feel of that magical glass perfume bottle) and then proceeds to idea.

When I first came up with the theme for these interviews, you seemed to be the perfect fit. Would you ever call yourself a poet of landscape, or of anything in particular?

Wherever I am, landscape matters very much to me, and of course this is apparent in my poems and in my children's books as well. Humans do so much to shape landscape, and landscape does much to shape us. Landscape is always in flux; and in considering it, we have also to think about time, continuity, dislocation, generations, the 'then and now' of it. To call myself a poet 'of anything in particular' seems somehow reductive. But there are themes and matters and threads that recur, of course. How could it be otherwise?

So, Kevin, you begin your life in Buckinghamshire, but spend a great deal of it in Norfolk. Of all the collections of your poetry, it’s the landscape and characters of ‘Waterslain’, which I find most evocative. Why did you decide to capture a piece of the past in that way, its community and characters?

In 1928, my grandparents bought a pair of fishermen's cottages in Burnham Overy Staithe in north Norfolk, and they retired there during WW2. Almost every school holiday, my sister Sally and I stayed with them for a week or two. The creeks and saltmarshes and the tidal island of Scolt Head became part of the rhythm of my life.

I was sixteen when I began to write poems: poems of fluctuation, you might say, about falling in love, and about the make-and-drag of the tides, and the saltmarshes. At first my poems were essentially personal and confessional; but during the 1980s, when I was also writing children's books including Storm (my ghost story set in North Norfolk), I began to think about some of the characters whom I had got to know during my childhood visits to my grandparents: the fishermen, the wildfowlers, the shopkeeper, and the indomitable Miss Disney.

Easterlies have sandpapered her larynx.

Webbed fingers, webbed feet:

last child of a seal family.

There is a blue flame at her hearth, blue

mussels at her board.

Her bath is the gannet's bath.

Rents one windy room at the top of a ladder.

Reeks of kelp.

I lightly disguised Overy Staithe by calling it Waterslain, and wrote a sort of child's eye view of these characters. They figured large in my imagination, and they still do! And, as you say, I set them and their village in the landscape where they lived the one where I live now, and love the most.

|

Seahenge photo by Andrew Rafferty |

Your recent collaboration ‘Seahenge – A Journey, take us through both landscape and memory, from your childhood museum in the Chiltern Hills, and then following the Northern Icknield Way and Peddars Way until you reach North Norfolk and the timber circle that became known as Seahenge. The last line of your afterword reads.

‘Whiteleaf – and North Norfolk – my headland, my heartland’

Do you see the book as yourself coming full circle and what made you connect Seahenge with your own journey?

A love and investigation of landscape quickly leads to memory. Most places are like inverse onions they have many skins. Or perhaps 'palimpsests' is a better comparison. They're surfaces that have been written upon many times, and some of the earlier marks have been erased.

When I was growing up in Whiteleaf, I was well aware of the Icknield Way - the prehistoric track that begins life as the Ridgway near Avebury and Stonehenge, leaps the Thames at the Goring Gap and runs through the Chilterns into Bedfordshire and East Anglia before playing itself out when it reaches the Wash. In fact, I often imagined traders leading their packhorses from Grimes Graves in Norfolk to Avebury, poor creatures with saddlebags crammed with the best (or most sacred?) flint in the county. And I think I knew that the track must have been used for centuries, millennia even, for sundry purposes secular and sacred; as much , no doubt by people on their way to some place of pilgrimage as by traders.

But of course I had no sense then that I would come to live in North Norfolk, and that the Icknield Way between Whiteleaf and Holme in North Norfolk would become, as it were, my lifeline.

|

Whiteleaf Hill and Chalk Cross |

In 1989 the photographer Andrew Rafferty and I collaborated on The Stones Remain, a book about Britain's megaliths and stone circles. While preparing a new edition, Andy asked me whether I would write a poem about Seahenge, first substantially revealed by tides in 1999.

So as well as stepping into the past, and the matter and mystery of Seahenge, I decided to follow my own lifeline, and found myself writing a sequence of poems leading from place to place, childhood to old age, and to some extent from material to spiritual, while at the same time being about changing scape, caught in time yet in its essentials timeless.

Your poems are such that often so subtle that a powerful phrase can take you by surprise. In your 2015 collection, ‘The Breaking Hour’, there are three lines which seem to reinforce the message of the poem ‘Lifelines’, in which you mull over the life that can inhabit a place when thousands of years of habitation have been and gone. At one point you actually say, ‘Look! They have not gone away. Not one of them.’ Is that a statement of belief? What do you feel about the presence of the long-dead in the land they leave behind?

If I write that I am continuously surrounded by presences, it may sound awfully claustrophobic or otherworldly, but it's not like that. I don't have a seeing eye, for better for worse, but I can't go anywhere without a very strong sense of 'those who before us weren't the children and women and men who were born and grew up and lived here and died here before me; who shaped and were shaped by this landscape. I don't think that this continuous awareness is strange or complicated; it has simply grown in step with the way I've become more and more interested in history, and in people! The dead are my companions. They have receded into silence, and have proceeded into silence, as I will. You ask what I feel about being part of this. I think I feel moved by it; and consoled by it. For the most part, I just observe, I just eavesdrop, and take it for granted.

|

The Dead are my Companions. Photo by Andrew Rafferty |

Of course, you first became known for your work on Norse Myth. Please feel free to talk about what inspired you about those particular stories, and perhaps especially the landscape?

As a translator of Beowulf - this in my twenties while most of my peers were gadding around to the Beatles - I grew to love the stubborn cast of the Northwest European mind, and to relish a landscape no less bleak than the Norfolk saltmarshes; the half-light of dark days, all gleam and glimmer.

But I really wasn't familiar with Norse mythology until, at the end of my twenties, W.H. Auden told me I should look north, familiarise myself with the myths, and think about retelling them - something in which I was also encouraged by the great Gwyn Jones, author of The History of the Vikings (OUP 2001)

There and then, if you please, I resigned my enviable job as editorial director of Victor Gollancz, and put myself in the hands of fate.

Looking back, this was the most decisive step in my writing life, but at the time it didn't seem like a difficult choice at all. Beset as I was by marital financial liabilities and with school fees to pay for years ahead, most of my family and friends thought I'd taken leave of my senses, and maybe I partly had. That's to say, maybe one partly has to. 'Writers must me mad!' I cheerfully set off for Iceland with my two sons, Kieran and Dominic, and camped there, surrounded by mountains and glaciers, stupendous waterfalls, thermal springs, miles and miles of lava and black grit.

In the myths, we hear about the nine worlds and the world tree, Yggdrasill - and we can imagine how the Norsemen visualised them. But the writers (above all Snorri Sturluson, of course, the great Icelander who was born in 1179 and was drowned in his bath in 1241) treat them as theatres of action; no more, really, than extensions of the landscape with which their readers and audiences were already familiar.

|

The Always Tree |

Because it was obvious how much the gods and giants and dwarfs and the inhabitants of the nine worlds were children of a northern landscape, because some of the deities were indeed embodiments of aspects of landscape and elements, and because I was writing for an audience relatively few of whom were familiar with it, I seized the opportunity to place these great stories in their physical settings.

You’ve been in a second collaboration for your second book of Norse Tales, with Jeffrey Allen Love, who has a particularly unique style, which is almost a form of shadow puppet art which is not afraid of either empty space, shadow and even total darkness. It’s a very interesting match, accompanied by your sparse but gleaming prose.

Different illustrators have approached the Norse myths in widely different ways. Amanda Craig (who seems at last to have resigned herself to quite liking my work) wrote about this succinctly:

'Jeffrey Alan Love's pictures add a monumental grandeur. Chris Riddell's elegant illustrations for Neil Gaiman's version of the myths emphasized the stories' beauty and mischief; the d'Aulaires gave them an appealingly colourful naivety; Brian Wildsmith conveyed character and emotion through a delicate web of pen and ink in the Lancelyn Green version. By contract, Love's craggy black silhouettes stamp a graphic power, mystery and dynamism on every page. All the gods are instantly recognizable, from Thor with his crude hammer to Loki, whose curling head-piece seems part jester's cap and part grasshopper's antennae as he crouches, leaps and persuades.'

|

Image from Norse Myths by Jeffrey Alan Love. |

What Jeff has to say about his dramatic and often fearsome roughs is that he works digitally in photoshop, as for him sketches are not about drawing but composition. What interests him is value, shape and edges. Then he can increase or diminish the sketch to see what works best; 'and I paint the silhouette with black paint or ink. . . and then I coat various brayers, paint rollers, socks, petrified sticks I've found on the beach, sponges, brushes, old shoes, my fingers etc. - just about anything can leave an interesting mark - with paint, and start distressing the image'.

When the art editor at Walker Books, Ben Norland, first showed me some of Jeff's artwork, I remember thinking that I had never seen anything so compatible with the Norse myths: their drama, their ferocity and absolutism, their darkness and next-to-nihilism, and yet withal their stark beauty.

'Yes,' said Ben, with a smile. 'I've written to him to say I think he was born to illustrate the Norse myths.'

The impact of a piece of art is immediate. It smacks you in the face, and then one investigates and discovers layers and subtleties. It's not the same with a piece of writing. It may be arresting from the start, but it creeps into one's mind and heart, and there it stays.

When I retell Norse myths and tales, I aim for clear, striking, simple, uncrowded, musical prose. But it's not for me to judge how well Jeff's artwork and my writing work together.

|

Kevin's sons, Kieran and Dominic, ready for a new adventure.

|

‘Stories from Across the Rainbow Bridge’ is a quite light volume in comparison to its predecessor. Having only space for five tales, how did you decide which to use and adapt and where did they come from? There’s remarkable contrast in there.

When you began adapting the Norse Tales, what were the things you most wanted to emphasise and re-capture for your audience?

Human beings feature in only a few myths - it's as if the gods are not particularly interested in us! But they do cross the rainbow bridge to Middle Earth often enough, and there are occasions when they assist or reward men and women.

I thought it would be interesting to bring together a few of these tales. One was first written down by Snorri Sturluson in the early 13th century; my sources for the others were early collections of Icelandic and other Scandinavian folk tales.

Family is a theme that occurs again and again, not just in your poetry, but in your novels like the Arthur de Caldicot series, ‘Gatty’s Tale’ and more recently your two novels of Solveig, the Viking girl, in ‘Bracelet of Bones’, and ‘Scramasax’. Your own family ties were and clearly are very strong. Was it only natural, do you suppose, that family have featured so much in your writing?

Yes! I love and support and honour my wife, my children and grandchildren, my sister and my extended family, and when I fail them I fail myself. But I'm also mindful, always mindful, and never more so than now on the doorstep of my eightieth birthday, with the wretched virus flying around us, of the truth of W.B. Yeats' great lines:

Think where man's glory most begins and ends,

And say my glory was I had such friends.

|

| Early memories - Kevin with his parents and sister Sally. |

Thank you again, Kevin, for both the interview and the gift of your wonderful poems. This second poem returns us to the theme you explore in the poem 'Lifelines', from your collection 'The Breaking Hour.'

BELONGING

Birds's Pightie and Bradmere

Shift.

Who remembers them?

I do, chirps sparrow. I do

screams swift.

Whin Hill Marsh and far

Wallow.

Who remembers them?

I do, croaks herring gull. Me

too, twitters swallow.

Dawling Lane. Brittle Breck

Who remembers them?

Me, squeaks sanderling. I do,

sings little lark.

Ah, these acres and green

lanes

dawdling and stretching.

The turning years have

stopped their names.

Yet listen. Look! Isn't it true

- tear in the fence, tear

in the eye -

that clump or muddy or thick

with dew.

they still belong to me and to

you?

|

Towards Scolt Head by Gillian Crossley-Holland |

Next month and for the month after that, I am delighted to say that I will be interviewing illustrator, writer and co-creator of the magical 'Lost Words' series, Jackie Morris. In the fist of these interviews on 16th December, we will specifically talking about project, its many inspirations and off-shoots. I look forward to seeing you then.

--

.Steve Gladwin - Stories of Feeling and Being

Writer, Drama Practitioner, Storyteller and Blogger.

Creation and Story Enhancement/Screen writing.

Author of 'The Seven', 'Fragon Tales' and 'The Raven's Call'