I’m not sure whether ‘You can’t judge a book by its cover’ is a proverb or a metaphor or a piece of advice. If it’s a piece of advice, I’ve always ignored it. And if it’s true than I wonder why publishers spend so much time trying to get the cover right and why it caused such a kerfuffle when Waterstone’s recently turned all the books round to show the blurb on the back.

Last month I wrote about the book which won the Carnegie in 1940, and Penny Dolan wondered ‘how the book worked with the readership rather than the library judging panel’. That’s a question that’s hard to answer after all this time, but it made me think about how I chose books when I was a child, and about the books I read and enjoyed myself.

|

| It's a book with children in it. I expect they're visiting from London. I would not have taken this off the library shelf, which is a shame because I might have enjoyed it. |

My period of peak children’s book reading came between 1960 and 1966. I read a lot of books in that time, but I never owned any of them. They all came from the library. I don’t know if I’m unique, but in my family, back in the 1950s and early 1960s we all read a lot but we didn’t own or buy books. Penny mentioned that most children’s books these days are bought by parents and grandparents. I’m sure this was true back then of those children who owned books, the ones who had the latest Arthur Ransome or Noel Streatfeild delivered to the end of their bed each Christmas. But my reading was completely unmediated by my parents, or by any adult other than the children’s librarian at my local library who chose which books to buy, if such a person existed.

|

| Same colour but a world of difference. |

And so I had two main ways to choose a book. The first was to look for anything by Enid Blyton and the second, deployed when I couldn’t find a Blyton I hadn’t read, was to look for something with a cover that looked equally exciting. If it was good, I’d then read everything by that author. Once I’d exhausted those possibilities (and there wasn’t an unlimited supply of my kind of book) I’d select books almost at random and read a bit. If the first page was good, I’d read the rest. I’ve never been a reader of blurbs.

|

| The promise of excitement |

|

| Even more excitement |

My lockdown reading of Carnegie winners has now taken me as far as 1950. Based on their covers there is only one of those winners that I would definitely have read back then, and it’s the only one I did read—Pigeon Post. The Arthur Ransome covers are an inspired piece of branding that makes them stand out, even today, from everything else around them. I might have read The Circus is Coming too, but it would have been in the third category, a browsed book where the first page hooked me in.

|

| No chance. Even a bit scary! |

I would definitely not even have opened The Radium Woman or Visitors from London. Sea Change by Richard Armstrong looks like the sort of book they’d give you to read at school and Agnes Allen’s The Story of Your Home is a book I would have been terribly disappointed to receive for Christmas, even though, as I’ve said already, books were not given at Christmas, or any other time, in my family. I wouldn’t have been interested in gnomes, either, or ponies, and the opening pages of We Couldn’t leave Dinah are way too ponyish for me, or rather, for the boy I was then.

|

| A pony and a stable? I don't think so. Why no evil Nazis on the cover? |

Back in the early sixties most, if not all of those early Carnegie winners would have still been on the library shelves for me to take home. I’m sitting here trying to figure out what I would have made of them back then if I had been made to read them, or if they had been read to me. (As far as I can remember we never had a daily story time at my primary school, and I didn’t have bedtime stories at home after the age of about five, but I had three younger sisters so you can see why!)

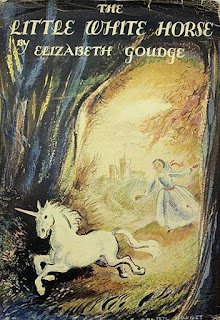

The main problem with many of these books for the me-back-then is that there is too much in them about adults. That would have stopped me for sure, so Eve Garnett, Eleanor Doorly, Kitty Barne and Eric Linklater all fail that test. It would have put me off the Noel Streatfeild too, but there’s enough fun and action to have made it work for me. The gnomes in The Little Grey Men are very old and the whole thing is a bit weird and Walter de la Mare is very weird and there are adults there too. Elizabeth Goudge’s The Little White Horse is a special case because it is very much, or would have seemed to me then, a girls’ book, not so much because it’s about a girl as because it goes on about loveliness most of the time, and even when people aren’t lovely you just know it’s going to turn out fine in the end. It’s a terrific book which I’ll write more about later, but ten-year-old me would never have read it. A girl and a unicorn on the cover! No way! (Oh, and quite a spoiler that as well.)

Anyway, by the time I was eleven or twelve the covers of the thrillers and detective stories my mother brought home from the library were more enticing than anything I could find in the children’s section and that was me done with children’s books pretty much for the next ten years. I don’t think I was so very different from many other children, then or now. I read what I wanted to read, and mostly the books I read were by writers who never won the Carnegie Medal—Enid Blyton, John Pudney, M Pardoe, Richmal Crompton, Laura Lee Hope (yes, I read The Bobbsey Twins)!

More modern readers, too, like to go their own way. Roald Dahl, Jaqueline Wilson, JK Rowling, none has won the Carnegie Medal, which I think tells you that if you really want to know about the history and pattern of children’s reading over the past 80 years, the list of winners of the Carnegie is probably not the best, and certainly not the only place to look.

|

| Now that's what I call a cover! |

And finally I have to admit that, although my taste has broadened a little since I was ten years old, if I want a book I can't put down I turn to the likes of Michael Connelly, Robert Crais, John Harvey, Ian Rankin, Sara Paretsky or, lately, Adrian McKinty. First the name, then the cover. And I love Dick Francis from his golden period in the 1960s and 1970s—another find from my mother's piles of library books.

If I'm browsing in the library or bookshop I still choose books the same way. First by the author, then by the cover. If it looks like my kind of thing I read a few paragraphs and that's enough for me to tell if I'll want to finish it. So, best keep those covers turned to the front, Waterstone's, at least as far as I'm concerned.

5 comments:

Really interesting post, Paul - and it brought back a lot of memories for me too!

This holds true with modern 10-13 year olds as well. I am always baffled when authors go on and on about what THEY want to write. What about what children want to read? And yes, I could use a number of books with airplanes chasing cars!

That was really fun to read. Thank you!

I read this post yesterday but almost dared not comment in case I was quoted :-)

That Madam Curie book does look highly sinister, and possibly truer than expected.

However, those early slip-jacket covers were created during a time - I believe - of paper shortages and on much simpler printing machines. I wonder when the now-iconic Ransome cover style (and branding) was first used for his books? (Pigeon Post was published in 1936 by Jonathan Cape and is the sixth in the series.) The b&w interior illustrations are meant to be by "Miss Nancy Blackett" ie one of the characters, which may be another child-friendly innovation.

Cover design now seems such a different world, with digital design and colour printing creating the range of cover styles and fonts and sizes on offer, many echoing other titles in the genre.

Besides, cover images are often tested by publishing & marketing teams, with proposed versions shown to the big buyers & supermarkets for their comments.

In the 1930's, covers were probably created & approved by a couple of staff members in the publisher's back office, maybe with the thought that that was good enough for children.

Thanks all.

Penny, you did set off a train of thought! The cover style of the Ransome books was set in 1931 with the publication of Swallowdale with the Clifford Webb illustrations. Ransome illustrated Peter Duck himself and from then on the books had the same style using Ransome's illustrations. The earliest reprint of the first two that I can find with the Ransome illustrations is 1939.

I think Enid Blyton herself may have had a lot to do with the fact that her covers are so bright and appealing. Whatever you think of her books (and Dawn Finch on her Twitter feed has posted a link to a 2018 piece in the Independent putting the negative POV) she had a genius for publicity. She didn't suffer from the wartime paper shortage either. During the six years of the war she published well over 100 books!

Post a Comment